Photo By Ron Sinfelt

Fall is the best time of year to a deer hunter. The weather still is hot in much of Florida, but hunters can still get into the woods and start looking for those elusive big bucks. However, to truly be successful, hunters need to have a good picture of what is going on with the Sunshine State’s deer herd.

“Overall, the deer herd seems to be stable,” said Cory Morea, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s Deer Management Program coordinator. “In the harvest data, we’re seeing that larger-antlered bucks are being harvested, which we expected since we implemented greater antler regulations.”

As the new antler regulations were developed a couple of years ago, biologists suggested that there be might a temporary “dip” in the numbers of bucks taken statewide. According to Morea, harvest numbers did reflect a small dip, but not as significant a decline as biologists expected.

“This was particularly true in Zone D,” Morea said. “This makes us think that a lot of hunters were already voluntarily following some sort of greater antler restriction than the statewide antler regulation.”

While there are a few diseases always present in the deer herd, they are not causing losses of any concern. The FWC gets some reports of deer being found dead in late summer and early fall from either epizootic hemorrhagic disease (EHD) or bluetongue virus, but nothing to be concerned about so far.

“When they (deer) get sick, they seek out water and often can be found dead in water,” Morea said. “We get a little bit of that each year, but because deer in Florida and much of the Southeast are exposed to HD every year at a continuous rate, the annual die-offs are generally pretty low. The last significant death event from HD was in 2012 and 2013.”

The other major disease of potential concern in Florida is Chronic Wasting Disease, but the FWC has not detected CWD in Florida at this time.

Dr. James Kroll and Pat Hogan discuss the impact of wind on deer behavior.

(Via North American Whitetail)

“We continue to test and monitor for the disease,” Morea said. “We try to get around 800 samples a year from wild deer and we have yet to detect it. That’s the good news. The bad news is that you can never say for sure that you’re CWD free; you can only say that you haven’t detected it. We certainly hope that we never detect it.”

With so many hunters and even non-hunters using trail cameras, the FWC often gets pictures of unique situations with deer and deer afflictions that might otherwise have gone unnoticed, which is good because it helps biologists identify different concerns regarding deer, including cutaneous fibromas (deer warts), which are skin growths that are gray or black in color that can be anywhere from half an inch across to more than 8 inches in diameter. Deer warts are caused by a virus and often disappear after a couple of months. They are found strictly on the skin of the deer and do not harm or affect the meat in any way. There have never been any reports of a hunter contracting the virus or developing warts after skinning a deer with deer warts.

“You can eat the meat, and there are no management concerns,” Morea said. “We frequently get a picture of a deer from a hunter wondering what’s wrong with it.”

Another oddity is arterial worms, which are adult nematodes that get into the carotid arteries of deer and cause lumpy jaw. Basically this is when deer gets food stuck in its jaw and forms an impaction, a small balloon-sized lump on one side of its

jaw. Once again, this has no effect on the quality or edibility of the meat of the deer.

“If you see one and would normally have harvested that deer, go ahead and process it and eat it,” Morea said. “There’s no reason to take them out of the population because none of these are conditions that are going to be passed on genetically to the deer’s offspring.”

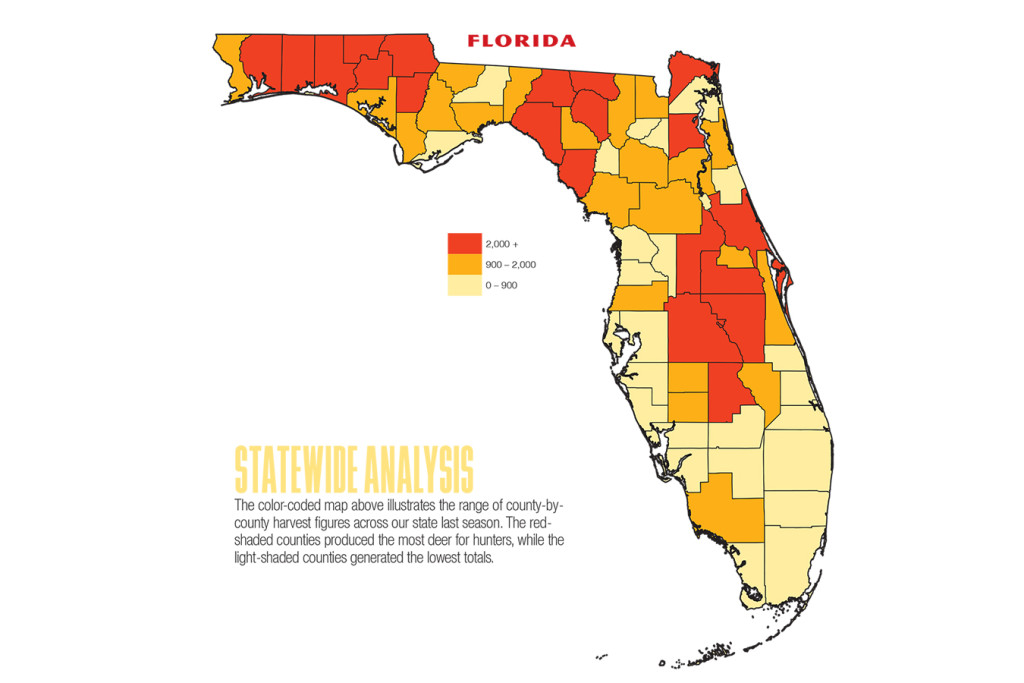

Morea says that in terms of general herd conditions, the Panhandle north of I-10, which is DMU 2, continues to do well in producing both numbers of deer and larger-antlered deer.

“It has good soils and a lot of agriculture, and it’s a part of the state where we also have higher deer depredation rates,” Morea said. “The area around Marion and Alachua counties and the area down around Polk County continue to do very well as they traditionally have.”

One rule change on public land is a restriction on taking antlerless deer from Joe Budd Wildlife Management Area. This rule was implemented because the deer population on that area has been declining over the past few years because of a hemorrhagic disease outbreak in 2012-13, as well as heavy antlerless deer harvest. Joe Budd is only one public area where FWC biologists are watching the deer herd to see if adjustments are needed in the future.

However, Morea expects no rule changes for the 2017-2018 season.

“This will be the third year we haven’t had any significant rule changes,” Morea said. “That was by design. When we did the big review of hunter preferences several years ago and made a number of changes, developed the Deer Management Units and made the antler regulations changes, and made all the other changes based on hunter preferences, we wanted a number of years to pass before we made any other significant changes.”

However, biologists still are listening to what hunters want regarding bag limits on both antlerless and antlered deer.

Additionally, the South Florida Deer Study is continuing, with biologists collecting significant amounts of good information. In fact, a wildfire recently burned through parts of the study area, so they are now getting good data on how deer move in relation to wildfire, as well as their survival during wildfire.

The South Florida Deer Research Project began in 2014 and will run through the end of 2018. Research sites consist of the Florida Panther National Wildlife Refuge and the Bear Island and North Addition Land Units of Big Cypress National Preserve (BCNP).

One goal of the project is to gain a better understanding of deer ecology in the South Florida environment, including how water levels, habitat differences, predation and hunting impact deer population dynamics. Another goal is to develop a monitoring technique that can provide reliable estimates of deer densities in South Florida habitats.

During deer hunting season, hunters may see a collared and/or ear-tagged deer within or close to the South Florida Deer Research Project study areas. Biologists ask that hunters not let the presence of a collar impact the decision to harvest a deer. If you would normally harvest a deer that happens to be collared, do so. On the other hand, if you would normally pass up that deer, do not let the collar influence that decision either.

However, if you harvest a deer with a collar and/or ear tag please call 239-657-8021 or email southfloridadeerstudy@gmail.com as soon as possible after the harvest. If you harvest the deer at a wildlife management area, and the area has a staffed check station, please check the deer there.

ADAPTABLE PREDATOR

Coyotes have been in Florida for quite a few years, but they have been increasingly in the news of late.

“They do take a few deer, but they’re mostly fawns during the fawning period,” Cory Morea said. “Studies have shown that they are having an impact on deer populations throughout the Southeast. That’s something we have to be mindful of and consider when we’re developing harvest strategies for deer.”

Back in the 1980s, Morea says, coyotes were expanding into Florida, but they weren’t prevalent throughout the entire state.

“Since then, they’ve gotten prevalent throughout Florida,” Morea said. “In the past decade or so, they’ve become more of an urban and suburban issue than they were before. The overall numbers have increased, and their geographic coverage has increased.”

Today coyotes have been documented in all 67 counties in the state. They are shy and elusive, and feed mostly on rodents and small animals, such as foxes, opossums and raccoons.

Coyotes adapt well to a wide range of conditions, fitting right into any environment.

In the 1980s, biologists were concerned that coyotes would mate with domestic dogs and produce wild “coy dogs” that wouldn’t fear humans and would occupy a top predator niche in the environment, but this has not materialized.

“Some of our greater concerns are hybridization with red wolves, where the two species intermix, but there isn’t anywhere in Florida that that’s happening,” Morea said.

The post 2017 Florida Deer Forecast appeared first on Game & Fish.