Photo By Ron Sinfelt

Things are looking quite good these days for deer hunters in the Volunteer State. Not only are harvest numbers up and holding steady, but the quality of antlered bucks seems to be on the rise as well. And that is not even taking into consideration the pending new world record whitetail taken in Tennessee last season or what would have been a new state record deer had it not been for the world-record-class deer taken.

The deer harvest last season was consistent with numbers posted over the past few years, although it was down slightly, but not statistically important. The harvest was 157,734 deer, down roughly 10,000 animals from the year before. This is not a sign of decline in hunter success, as the difference is negligible given the conditions last season.

The weather was unseasonably warm last year, especially in September and October, which most likely impacted both deer movement and hunter effort. Plus there was a very good mast crop over much of the state. This means there was plenty of forage and deer did not have to move as much to find food. This obviously decreased deer sightings and shooting opportunities for hunters. So overall, it was another very good hunting season.

Dr. James Kroll and Pat Hogan discuss the impact of wind on deer behavior.

(Via North American Whitetail)

It was also a very healthy season for deer according to Tim White, wildlife biologist with the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency. There were no significant disease outbreaks, such as bluetongue virus or epizootic hemorrhagic disease (EHD). EHD occurs naturally and there are a certain number of deer affected every year, but last season occurrences of the disease were limited. EHD is spread by biting midges, which are very small flies. The most significant outbreaks of EHD occur during years with very dry conditions. Deer are often congregated near available water and numerous animals are bitten while grouped together.

Of even more importance than EHD infections, the deer population remains free of chronic wasting disease. This disease is exponentially more dangerous than bluetongue and EHD, but so far Tennessee has been fortunate to not show signs of the disease being present, although it has been found very near its borders.

It has been found in wild deer in border states including Arkansas, Missouri, Virginia and West Virginia. The disease has increased in eastern states in recent years and states in or near infected areas are conducting surveillance and testing each year. In Tennessee, the TWRA has really ramped up efforts to monitor for CWD in the state, recently increasing the number of deer tested each year from 200 animals to 2,000 animals. The TWRA also put in place a CWD surveillance and action plan — a predetermined plan of action should CWD be found at some point in the future in the Tennessee deer population. It is obviously better to have a well-thought-out plan in place if CWD finds its way into the state rather than be caught unprepared.

Another item of particular importance to the TWRA is the antlerless harvest and ongoing questions about how to determine an antlered deer from an antlerless deer. For many years, an antlered deer was considered any deer with at least one antler 3 inches in length or longer. This regulation led to a large number of young male deer being legally harvested as an antlerless deer. In an effort to protect some of these male deer, in the hopes of recruiting more antlered bucks onto the landscape, that regulation was recently changed.

The new regulation defines antlered deer as male or female deer with antlers protruding above the hairline. Antlerless deer are defined as female or male deer with no antler protruding above the hairline. This new definition requires that any deer harvested with antlers protruding above the hairline to be counted toward the statewide limit of two antlered deer.

White says the initial season with this ruling in place made no difference in the harvest of young male deer. However, there was a good amount of discontent from hunters, especially from firearm hunters. Bowhunters may be able to see antlers protruding above the hairline at close range, but it is very difficult to determine a first-year buck from an antlerless deer at longer distances. According to White, the TWRA is continuing to monitor the antlerless harvest and the regulation defining an antlered deer may be reevaluated or changed at some point.

It is very important to note that the goal here is not to limit hunters, but actually quite the contrary. By finding a way of protecting young bucks, it gives them the opportunity to grow and add to the antlered population in future hunting seasons. As with dropping the bag limit on antlered deer from three per season down to two per season, it is about providing a better quality hunting experience and balancing to the herd ratio. A more balanced herd means more bucks and a healthier overall deer population.

Another bonus of a reduced buck bag limit and a more balanced herd is the uptick in buck quality. Each year with a reduced buck harvest means more antlered deer left to grow larger next season. This results in an older age-class of bucks and increases the quality of antlered deer in general as well as the potential for trophy animals. The TWRA is not specifically managing for trophy deer, but it is definitely a positive attribute to managing for better quality and a more equal buck to doe ratio.

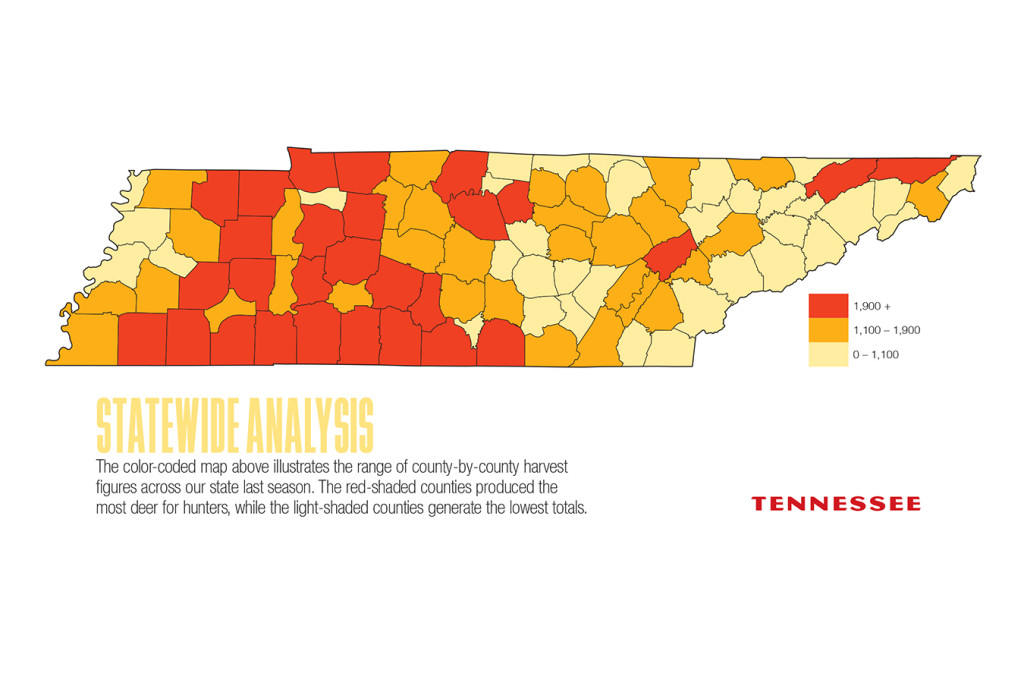

Tennessee has a lot of diversity across the state, and as such, there are major differences in the number of deer in areas and the amount of deer a particular habitat can support. There is a huge difference between the Mississippi River Alluvial Valley in the west and the Appalachian Mountains in the east.

According to White, there are no particular areas of concern, but the mountainous regions are going to hold fewer deer than the western and central portions of the state simply due to the natural habitat limitations of the mountains.

The mountainous counties are more susceptible to impacts from mast crop failures. In the western and central portions of the state, a failure of the acorn production in a given year is not quite as significant because the deer have farm crops and other food sources to utilize. However, a shortage of hard mast in the mountains means deer must rely more on browse, and a total mast failure, especially in a harsh winter, can mean a much bigger impact on deer numbers, not only through mortality but also in reduced fawn numbers the following spring.

Deer numbers are best in the western and central portions of the state. The counties with the highest harvest figures are found in Region 1 and Region 2. Along the Mississippi River corridor, the bottomlands provide a very fertile habitat providing deer with all they need to grow and stay healthy. The central portion of the state also has an abundance of farm land, which is a real boost to the health of the deer herd.

Overall, the deer herd is in excellent condition and this season is shaping up to be another great year. Of course, deer numbers are not the only deciding factor in how the season plays out. Weather conditions, both good and bad, are a major component in hunter success and deer harvest numbers. Very bad weather, especially during peak hunting dates, dramatically decreases hunter effort and subsequent success. Likewise, good, weather conditions throughout the hunting season often leads to great hunter success and inflated harvest figures. Barring anything extreme, hunters should expect another terrific season with good numbers of deer on the landscape, along with plenty of success.

The post 2017 Tennessee Deer Forecast appeared first on Game & Fish.