If sometime in the course of the last five decades you found yourself sitting next to George Lepp on an airplane, or attending one of his workshops, or if you bumped into him on a mountain trail, chances are he taught you something about photography. It’s not just because he’s a world-class outdoor photographer and educator, but thanks mostly to his limitless exuberance for the medium and sincere passion for helping others. Photography is in his bones, and he’s made an art of sharing the knowledge and experience gained over the course of his 50-year career. In recognition of that, the North American Nature Photography Association (NANPA) is honoring him with a lifetime achievement award.

“Not only is George Lepp one of the greatest nature photographers of all time,” says NANPA Executive Director Susan Day, “he has spent most of his long career embracing new techniques and generously sharing his extensive knowledge with others. Before the internet and blogs, photographers studied George’s magazine articles, how-to books and quarterly newsletters to glean information about his techniques and tips. George is an eternal learner who has always been a step ahead of the pack in trying new gear, techniques and technology—and setting trends. George embraces change and adapts. He’s a founding member of NANPA and has been active in many roles since 1993. His willingness to share has inspired and guided generations of photographers to reach higher levels on their image-making journeys. NANPA is proud to honor George with our highest award.”

Lepp began his 50-year nature photography career in grammar school, when he was recruited to help produce a school newspaper. He’d never taken pictures, but he quickly became proficient with a Crown Graphic and darkroom processing. In high school, he shot family photos and picked up occasional freelance newspaper assignments. In college, he studied fish and wildlife management and spent his summers working for the U.S. Forest Service, kicking off a career that would be spent in the outdoors working for the preservation of nature.

Lepp has earned his keep as a professional photographer ever since returning from a tour of duty in Vietnam and completing his degree in photography at Brooks Institute. He has continued to utilize the publishing knowledge he gained as a student and in the military by writing his “Tech Tips” columns for Outdoor Photographer and publishing a quarterly newsletter since before the internet made such things easy. He has taught classes and led workshops for decades as well. Lepp has worked hard to share his knowledge at every step throughout his career, and it continues today in collaboration with his wife, Kathryn, a writer, editor and former university administrator. They’ve published three books and hundreds of articles together. Lepp calls her his “perfectionist.”

At the core of Lepp’s long and fruitful career may simply be his persistent ability to solve a variety of problems—from the creative to the technical, in individual photo setups encountered on any given day as well as with the larger movements that shape a career. This, too, he says, has been guided by familial influences.

“My father was a machinist,” Lepp explains, “and he could figure out things. He didn’t have any education, but he was smart, and so he would work his way through the problems to solve them. My photography has sort of been that way. All of these things I’ve developed have been to solve problems to get the kinds of pictures that I want.”

Some of the things Lepp has developed are highly technical pieces of equipment. For instance, the projected flash unit that utilized a Fresnel lens to throw a portable flash over greater distance with less falloff—something that is immensely useful to a wildlife photographer. The same technology is now integrated into most speedlight-style flashes, but at the time Lepp was breaking new ground.

“I made it for myself and used it to take pictures,” he says. “And, of course, I wrote about it. The next thing I knew, people wanted them. Talk about jury-rigged, but it solved the problem. That was one of the things that kind of developed out of the need to solve a problem. The other was a macro bracket.”

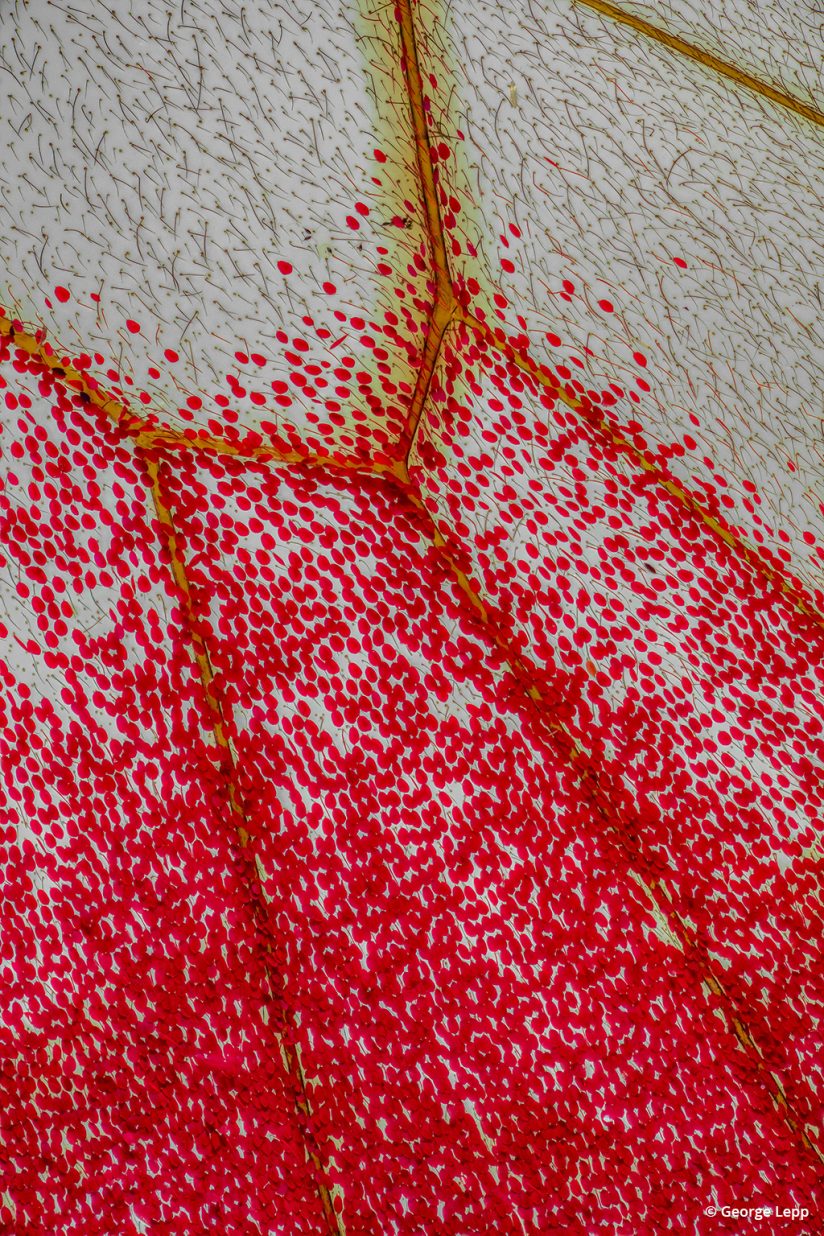

Ever the innovator, Lepp next developed a macro flash bracket that allowed for the use of two synchronized flashes for close-up photography. His camera manufacturer contacts at the time said it couldn’t be done, yet he did it. The Lepp Macro Bracket was ahead of its time and combined Lepp’s affinity for macro photography with his passion to push further, to do more while testing the limits of the medium. It led him for a time to preside over his own photographic equipment catalog.

For as technically progressive as he is, however, Lepp is not a run-of-the mill gearhead interested in cameras for cameras’ sake. His mastery of technique and embrace of technology is always in service to the image.

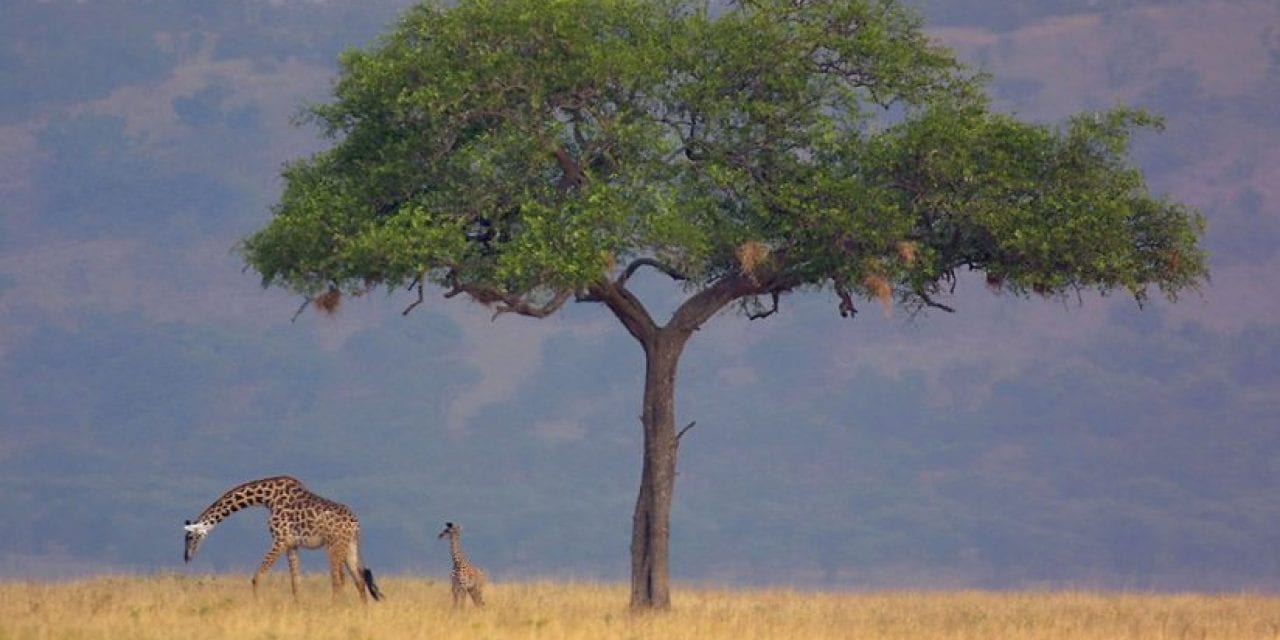

“For me, photography’s purpose is to show something that people haven’t seen before,” he says. “My philosophy about nature photography has been that it’s a window into the natural world. I’ve been in Yellowstone on the side of the road with a super long lens or something like that and people…It bugs me that people are more interested in my equipment than they are in the natural world that we’re out there experiencing and photographing.

“Natural history is a secondary and very important aspect of what I do,” he continues. “And I learned from a National Geographicphotographer, if you don’t have the natural science, you’re not going to be very successful. So I do a fair amount of research and talk to people about the subjects and so forth. The nature aspect of it is tied up and involved with the photography. A lot of times, the people who come to look at what I’ve got my camera trained on aren’t really photographers, so now I’m the local naturalist.”

Whether he’s explaining a photographic technique or discussing the biology of an eagle’s nest, Lepp is more than happy to help. In fact, he finds himself regularly conducting impromptu workshops with interested passersby. “All the time,” he says. “I’ll be out in the middle of a shoot someplace, and the next thing I know I’m running a class with two or three people who have shown up to do the same sort of thing. If there’s something I can help somebody with, I’m going to help them. And when they figure out that I have real information for them, then it gets to be very interesting. It’s what I do. It’s what I’ve always done.”

With his willingness to help and his preference for technique in service of subject, Lepp has his priorities straight. Sure, he’s excited about new equipment and techniques, but only inasmuch as they allow him to take better pictures, to communicate more clearly. It’s been this eagerness, this drive to see what’s next, that’s kept him going all these years and that still motivates him today.

As one of Canon USA’s first Explorers of Light, he’s had early access to every new thing in photography. “My more than thirty-year association with Canon has been one of the most productive and rewarding relationships of my career,” he says.

“It’s even more exciting today than it was at the beginning,” he says. “And after doing this for 50 years, you’d think I’d be burned out. I’m somewhat burned out on traveling in airplanes but not the stuff in my office, the work I’m trying to accomplish right now. When Canon hands me a new camera, I send them pictures and they say, ‘What the hell are you doing with our cameras!’ They’re happy about it! We just got the EOS R mirrorless, and so I’m all excited about the autofocus and 4K video.

“You see something going in a direction, and you go there,” he says. “You move through those things that you have to. That’s basically what everything that we do today is, this constant transition into the next thing and the next thing.”

Looking to the future, Lepp is particularly excited about the combination of stills and video. “I’ve been messing with 4K video where I’m taking frame grabs out of it,” he says. “If you give me a 6K or an 8K camera that is not a huge camera, that is not $20,000 or $30,000—which an 8K camera today would be—I now have 60 frames per second, a frame that I can make into a print, and I can get that exact piece of what I want to pull out. I can do 14 frames per second right now, but that’s not good enough. I want to do 60 frames per second. This is the direction that I think things are going. In fact, your iPhone does that now. Your iPhone takes a series of images; when you take one picture, it actually takes a bunch of them, and you can scrub through those and you can find the one when the person didn’t have their eyes closed. We’re going to see more of this. You can take that little bit of video, and you pull that out and it’s equivalent to an 18-megapixel camera at 6K. It’s a tremendous amount of information per frame.”

“So many photographers hear me saying this,” he continues, “and they say, ‘So photography as a skill is pretty much going to die?’ And I’m saying, ‘No, good photography is not. Capturing information is going to be even better.’ But straight photographers will say, ‘Well, you’re cheating.’ Yeah, I cheat all the time. I try to use that cheating to give me real, truthful pictures. It’s not like I’m trying to put them together in a composite of something that wasn’t actually there. I’m using the technology to solve issues.

“Being a nature photographer,” Lepp says, “you run into problems. The person who gets the best picture is the person who solves the problem the best.”

NANPA will present George Lepp with its Lifetime Achievement Award at the Nature Photography Summit in Las Vegas, February 21-23, 2019. For more information and to see more of Lepp’s work, visit his website at georgeleppimages.com.

The post A Life In Pictures appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.