Females may only be fertile one day a year, limiting this lemur’s ability to rebuild fragmented populations.

LEMUR ISLAND, MADAGASCAR

(Photograph by Joel Sartore / National Geographic Photo Ark)

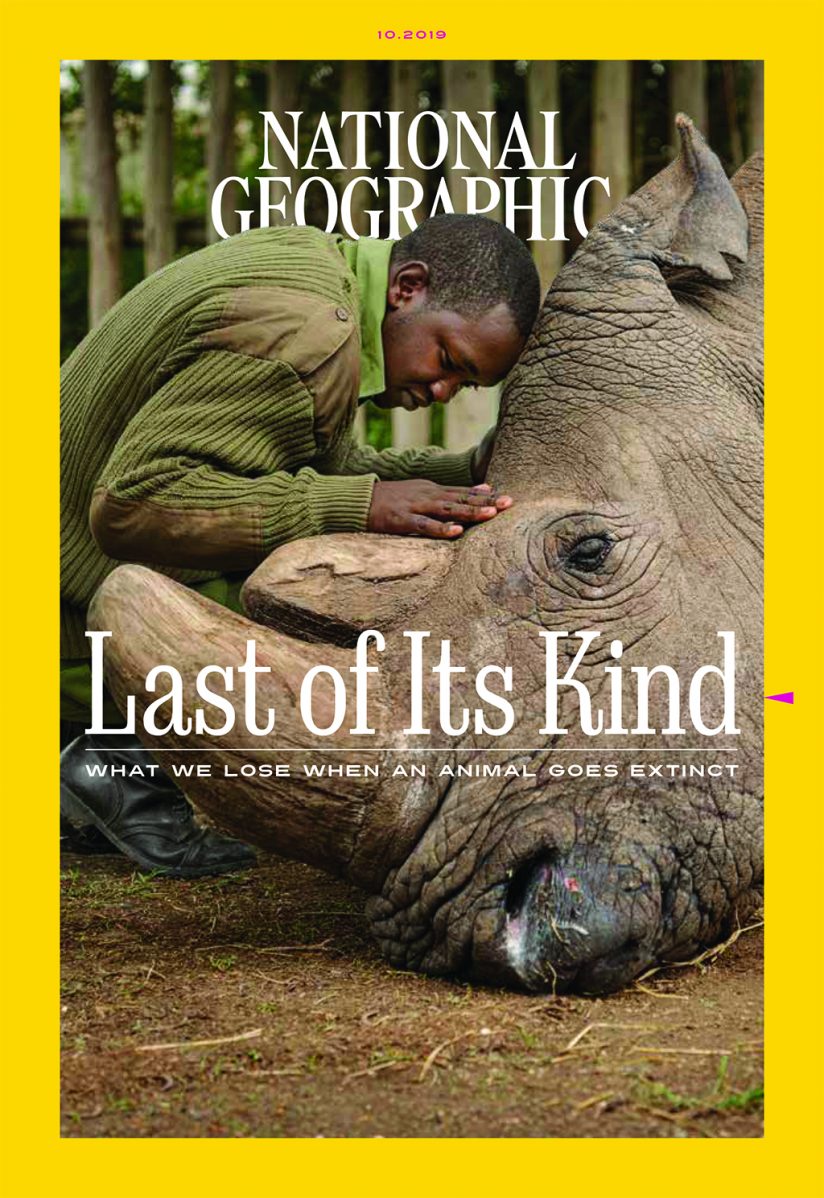

The cover of National Geographic’s October single-topic issue on extinction features an image of “Sudan,” the last male northern white rhino. Taken by Ami Vitale, the heartbreaking image shows wildlife ranger Joseph Wachira saying goodbye to and comforting the rhino in his last moments of life at Kenya’s Ol Pejeta Conservancy.

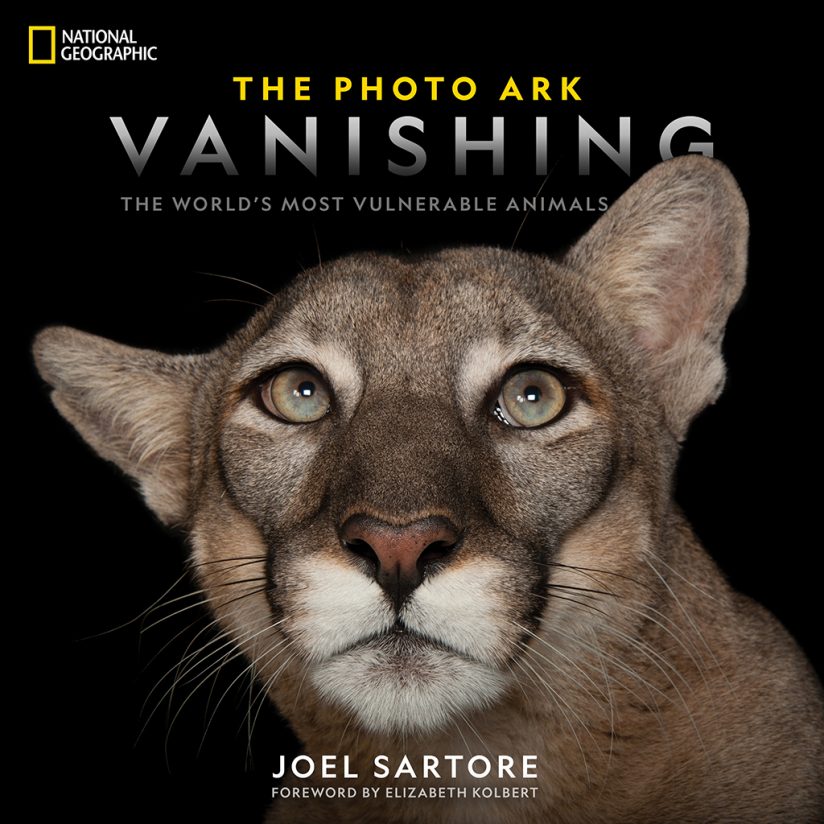

Images like this are far-reaching in their urgency, and that’s why Joel Sartore, a wildlife photographer and National Geographic contributor, has dedicated the past 13 years to capturing images of every species of animal in captivity to help save them before it’s too late. Sartore’s work is featured in the same issue, in an article entitled “Vanishing,” which takes a look at “what we lose when animals go extinct.”

Sartore has a long history with the magazine and conservation photography. “I did about 30 stories over 17 years as a field photographer for National Geographic,” explains Sartore. “I was working on one on Alaska’s North Slope when my wife found a lump in her right breast, and it turned out to be breast cancer. That was about 14 years ago, and she’s fine now, but it gave me a year to be at home and think about the fact that magazine stories kind of come and go in a month when the next issue comes out.

“I was seeing a lot of small creatures that were never really going to be noticed before they went extinct. I’ve done a lot of conservation work for National Geographic over the years and figured that, since a lot of these animals are physically small and may live in muddy water, or in the soil, or high up in the trees, maybe the easiest way to see them would be to isolate them on black or white backgrounds so we can really look them in the eye and get an idea of how beautiful they are and realize that they have a basic right to exist.”

And that’s how Sartore’s ongoing Photo Ark project was born. “It’s not only a large archive, but it’s also designed to lessen the impact of the extinction crisis,” he explains. “Right now, people are really consumed by politics and celebrity and the price at the pump and who won the ball game, when really the house is on fire if you think about it—the Amazon is literally on fire,” says Sartore. “We have to start thinking about the fact that when we destroy nature, we destroy ourselves.”

The setups for shooting Photo Ark were designed to accommodate animals of different sizes. These setups allow Sartore to not only work quickly to reduce stress on the animal, but also to not put a focus on the animal’s size, as every creature, from an ant to an elephant, has an important role in our planet’s ecosystems.

For small creatures like a Dakota skipper butterfly or the mouse-like long-eared jerboa, Sartore uses a small tabletop shooting tent that has a hole for a camera lens, which is all the animal sees and therefore helps keep it calm. For mid-sized mammals, like a black-footed ferret or a bonnet macaque, Sartore often uses a shooting crate system. This wire cage has a sliding front door and a five-inch hole for the camera lens. It also has reversible boards that are black on one side and white on the other for quick background changes.

For large birds like penguins and vultures, Sartore’s team uses a big shooting tent where, again, the animal only sees the camera lens. For large animals, such as a bison or critically endangered tiger, the setup requires an off-exhibit, enclosed space at the animal’s zoo or rehabilitation center that can be painted black or white before the shoot. Even aquatic animals get their day in the spotlight with the use of different-sized photo tanks.

After just over 13 years of this, Sartore has documented an impressive 10,000 species. “We figure the world has between 12,000 and 15,000 species in human care in aquariums, zoos, wildlife rehabilitation centers and with captive breeders. So, another 10 to 15 years should do it. We have to go farther to get fewer now, but we keep going.”

A recent photo trip took him to an unlikely place—his brother’s house in Omaha—to photograph a vesper sparrow. Sartore says the sparrow is “an unusual migrant through the Great Plains that’s being brought there by a wildlife rehab group to get its picture taken on my brother’s kitchen table.” Although common in the west, the bird’s populations are declining in eastern parts of the United States, likely due to habitat loss.

After that, it’s off to Colorado to photograph the mountain-dwelling pika, a small but tough mammal that’s a close cousin of the rabbit. These creatures generally thrive in their cool and moist high-mountain homes, but climate change is bringing warmer temperatures to their habitat. Even temperatures as mild as 78 degrees Fahrenheit can cause them to overheat and die. And already living in high altitudes, they have absolutely nowhere else to go. Although they’re not officially listed under the Endangered Species act, the National Wildlife Federation says they could go extinct without protection.

Sartore is a Nikon ambassador, so for the project he has predominately worked with the Nikon D850 for stills and the Nikon Z 7 and Z 6 for video. His team often has to travel with the smaller shooting tents and backdrops, in addition to LED lights and tripods. Larger shoots have Sartore traveling to places like Indonesia, Australia or Brazil, where the gear he can bring becomes more limited.

But it’s not the travel or gear limitations that ended up being the biggest challenge when working on this project. “For me,” Sartore says, “the biggest challenge is always getting the public to care, to turn their attention away from their smartphones for a minute to realize that as all these other creatures go away, so could we, we could lose a substantial portion of these animals to extinction in the next 20 to 30 years. And it will really alter how we live. So, the Photo Ark is really my desperate last-ditch attempt to use my work to try to get people to pay attention.” He adds, “We’re not exaggerating the nature of this problem. It’s really going to affect us all in a very negative way if we don’t learn how to preserve some of the wild spaces that are left on the earth.”

The nature of conservation work often means that your subject may be the last of a species, much like Sudan on the cover of the latest issue of National Geographic. “It’s very touching when you meet the last of something, or something that you’re pretty sure will go extinct,” says Sartore. “There was a rare tree frog that I met at the Atlanta Botanical Gardens years ago that has since passed away. It was the last of its kind. We’re seeing an animal or two every year that’s probably going to be gone within the next five years. So, it’s a very weighty thing and it makes me feel like it’s a big honor to tell their stories. It inspires me to do more.”

With photographers like Sartore as inspiration, it’s important to know that we don’t have to be regular contributors to a national magazine or have the means to travel the globe in search of subjects to make a difference. We can all begin locally, seeking out opportunities near home that we’re passionate about and use photography to help save wild places and wildlife. “I would really encourage your readers to know that what they do can matter,” says Sartore. “It’s not enough to photograph the butterfly on the flower anymore. You’ve got to photograph the butterfly with the bulldozer coming in behind it, to try to stop it and get wild places preserved before there aren’t any left. I think it’s really important for everybody to have some sort of project that makes the world a better place. And photography is a great tool to start with and you can really change the world with it.”

Sartore’s Photo Ark project and National Geographic’s October issue center around encouraging people to want to make a difference and provide the inspiration and tools for people to begin their own project. “I think it’s deep in human nature to want to help, but first we have to know what the need is,” explains Sartore. “And nobody’s going to save anything if they’ve never met it, if they don’t know what it looks like or that it even exists. So that’s where we come in. We hope to inspire people and not bum them out. We hope that they get fired up and want to actually save stuff close to home. There’s environmental work to be done in every town.”

How can you support the Photo Ark project? Go to www.nationalgeographic.org/projects/photo-ark and www.joelsartore.com. Follow Sartore on social media and share images from the project. Prints and copies of the Photo Ark books are also available for purchase.

Images in this article are from the October 2019 issue of National Geographic and the book, The Photo Ark Vanishing: The World’s Most Vulnerable Animals.

The National Geographic Society offers a campaign that gives readers the option to help save species by taking the National Geographic #SaveTogether pledge at NatGeo.org/SaveTogether.

The post All Creatures Great And Small appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.