Process allows researchers to monitor changes in survival, abundance and movement over time.

By Tim Lyons and Mark Vrtiska

Canada geese are perhaps one of the most easily recognized birds in Nebraska. From record lows in the 1960s, the goose population in Nebraska has rebounded, and geese are now common throughout the state. This growth has allowed increased recreational opportunities for hunters and wildlife-watchers, but also created problems in urban areas. Effectively managing the goose population, whether to sustain recreational opportunities or mitigate a nuisance, requires data.

To collect that data, biologists from the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission traverse the state to capture and band Canada geese during the last few weeks of June each year. Adult geese are in the process of replacing their feathers (a process known as molting) from last year and young geese born the current year are growing their new feathers. During this period, geese are unable to fly and are easily captured.

Biologists capture the geese by herding them into a small corral. Once captured, geese are aged (juvenile or adult), their sex is determined, and a metal band is attached to their leg. This band contains a unique combination of numbers that identifies each individual goose. That number, as well as information about each bird’s age, sex and location of capture is reported to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the federal agency in charge of organizing and managing all bird-banding data in the United States.

However, that is only the start of the data collection process, as a band must be reported, most commonly by a hunter after harvesting a banded bird, before that band can tell us anything. When a band is reported to USGS, scientists there enter information about where and when the band was encountered into their database, which they then make available to biologists. These details provide a wealth of information that Game and Parks and other state and federal wildlife managers can use to make management decisions.

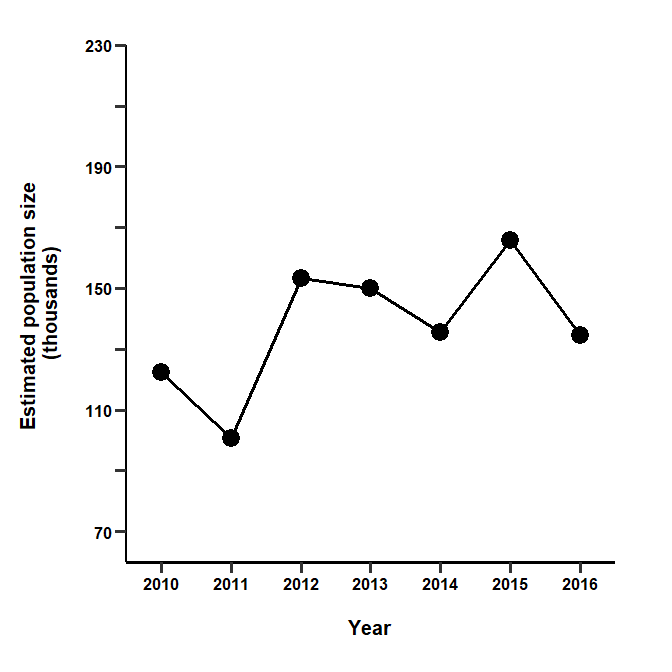

Game and Parks uses the banding and recovery data to better understand and monitor changes in survival, harvest, abundance and movement over time. For example, over the past 20 years, harvest regulations in Nebraska have liberalized, allowing for longer hunting seasons and increased bag limits. Banding and recovery data show that through this time harvest has increased and survival has decreased, but generally stabilized following each new regulatory change. More recently, estimates of population size since 2010 show no evidence of substantial declines. This suggests that current harvest regulations are not adversely affecting the population overall and may even be helping restrict growth.

When bands are reported with detailed information about where they were recovered, it also provides important information about movements of geese, both into and out of Nebraska. Currently, most geese in Nebraska do not leave the state on their fall migration. In fact, banding data show that most geese from Nebraska are harvested in Nebraska.

Decisions based on data and evidence are the hallmark of wildlife management in North America. Banding programs help to provide that data. But because it’s not until a band is reported that it tells managers anything, it’s really hunters and others who report bands who are collecting the data necessary to monitor changes in abundance, set harvest regulations, and ensure managers have the information they need to make the most informed decisions they can. ■

The post Banding Canada Geese appeared first on NEBRASKALand Magazine.