Always an outdoors column on the move, this week we go electroshocking catfish in Attleboro, Ma., find out how much you can learn by looking into a five gallon bucket and enjoy a quick discussion on Napoleon’s wallpaper.

Seriously.

Corralling a slippery eel

It’s difficult to connect an ankle deep river winding past a graveyard and an elementary school with striper fishing in Narragansett Bay. It’s also hard to see things hidden in plain sight, like a trash can at the town beach or a silent stream percolating up from dark soils and gravel. Often it seems impossible to put river pieces together when they are camouflaged with urban sprawl, golf courses, highways, culverts and abandoned brick mills shielded by chain link fences. But then, right before our eyes, below a canopy of elms and maples, six inches of riffle can hold more wonder than you might imagine. The Ten Mile River runs from its industrial roots in Foxboro’s Bungay River, threads south to Pawtucket before heading for the Seekonk River and Narragansett Bay just outside of Omega Pond. What happens here and there matters to both and that’s why the Ten Mile River Watershed Council watches so closely.

Spaceman walking a river, zapping fish with guidance…

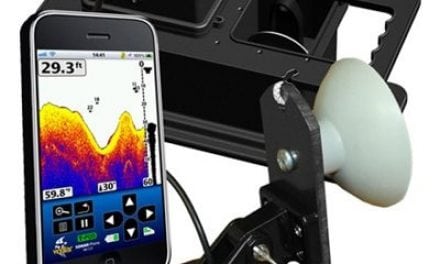

On yet another perfect and clear Saturday, President Ben Cote, past president Keith Gonsalves and Education Director Kassie Archambault brought together a small group of volunteers to catalog the river’s fish population. After some basic training, we were in the water supported by a team on land ready to measure photograph and catalog the catch. Electrofishing a slow dance: swing the wand to stun the fish, sweep in with a net, pass the net back to secure the quarry into a bucket, keep stepping sideways, don’t miss anything. The annual study serves to identify fish which either live in this stretch below the impounding dam, like bullnose catfish or migratory species, like catadromous American eels who, for no other reason besides that no one has stepped up to take the dam down, can go no further. Algae had painted nearly everything green, except the cement walls which locals had previously detailed with spray cans.

The dam wall is a remnant of our industrial past when Attleboro was a thriving mill town and the Knobby Krafters mill built hardwood shuttles for weaving looms further downstream, like Slater Mills. The cloth trade required water for power and for disposal so rivers paid the price of progress. Volunteer Dan Goulet said, “When I was a kid, the river was different colors, mostly green.” In the early 1800’s Scheele’s Green and later, Paris Green, were pigments produced for dying clothing, childrens toys, candles and wallpapers. Washed out at day’s end, it flowed down countless rivers leaving behind chemical footprints of arsenic, copper and salt. Paris green, a toxin named for its use to kill rats in the city of light, was sprayed on streams and lakes to control mosquitos. For the sake of history, Napoleon Bonaparte was no fishermen, nor did he much enjoy eating such, but his exile on St. Helena were tastefully wrapped in handsome wallpapers painted Scheele’s green and gold. Even his bathroom with its large copper tub, was papered with arsenic based dyes which leached into the air as his endless soakings kept the confines damp, steaming away his purgatory. Soon after, Napoleon passed from stomach cancer, his hair heavy with traces of arsenic.

Back on the Ten Mile, the team moved north, collecting pumpkin seeds, bluegills, golden shiners and white suckers.

Quite a catfish

Netting a 68mm brown bullhead catfish was exciting.

A tessellated darter was a real catch. Giving Keith a break from the backpack’s weight, Tim took over for the run to the dam. Buckets were passed, measurements taken, notes recorded. These surveys are real citizen scientist opportunities where an eighth grader works closely with a biologist to show what clean waters and respected rivers can hold.

It was real joy to put fish into an orange bucket.

In the sagging cement edifice’ slight shadow, the river seemed to grow cold, evidenced by our surroundings of fading Bud Light Ice case, Chill Zone cups and wrinkled Gatorade Frost labels. Intermingled with slimy black rocks, rotting limbs and crumbling cinder blocks was the big one, not a fish but an eel. Eels have that mysterious fantastic life cycle where they live in freshwater lakes and streams for years before they head for The Sargasso Sea to mate and perish. More fantastic is the young elvers have been blessed with a strand of DNA to guide them to their natal stream. There is also real joy in not having unravelled every natural mystery.

Just below the dam one was zapped and netted, only to have an escape in the scant few seconds between net and bucket. “Now we know there are still eels here!” exclaimed Tim. If measured it would have been eight or ten inches and as a second, smaller eel was sighted in the same area, that’s sufficient evidence of a population and another reason to celebrate Nature and the Ten Mile River volunteers. Can they take all the credit for an eel? No, but there are three fish ladders south of this dead beat dam that have allowed the eels to get this far and their hands and voices have labored diligently to make restoration a real event, something entire communities are now celebrating.

Steady hands and lots of eyes

Dave added, “We enjoy a sense of ownership, this is our neighborhood”. He recognized how buildings on urban rivers were built with their backs to the river. And there were lots of pipes to make things disappear. Now buildings are starting to have their eyes on the water, a welcome course change recognizing the importance of passive recreation and that rivers are something to celebrate. That may be what the Ten Mile River Watershed Council does best, help us celebrate what’s right in plain sight.

This stretch of the Ten Mile is a shallow oxymoron. Volunteers work tirelessly to keep her clean while fresh trash collects in dam corners and on low branches. A young fisherman casts an eight dollar frog lure for largemouth bass while a burned bottom of smooth stones caps heavy metals, toxins and rusts of an unconcerned era driven by greed and the facade of progress. Lightning fast eels survive behind rocks draped in garbage bags.

Happily standing up to his ankles in a miniature riffle, Keith told me, “It’s not easy. This requires a lot of dedication. You have to push hard.” The Ten Mile River is a work in progress but a success nonetheless quantified by this spirit of renewal from hard work.

I could have walked that river all day.

This piece originally appeared in the Southern RI Newspapers. © 2017 todd corayer