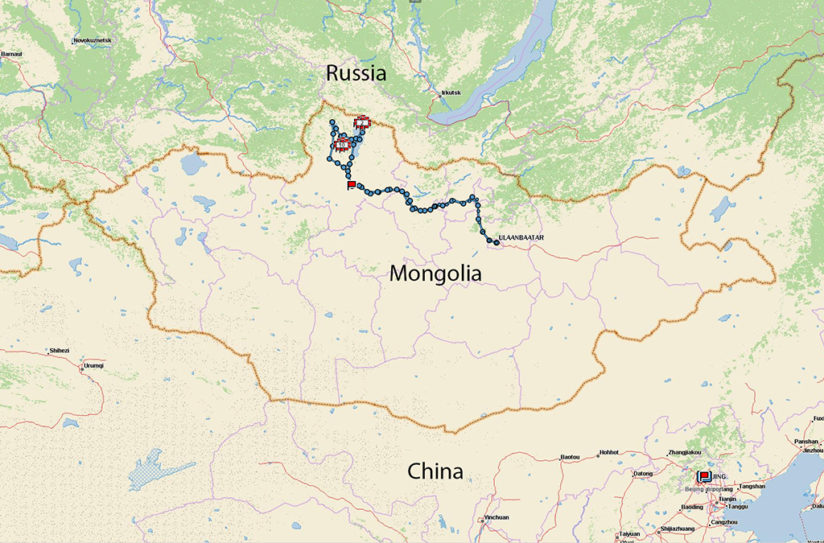

Mongolia lies nestled between Russia to the north and China to the south. At roughly 600,000 square miles, it is the world’s 18th largest country by area. The total population is about 3 million, and about half of those live in the capital city of Ulaanbaatar. Most of the country is sparsely populated, wild and beautiful. Mongolia has been an independent county since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.

I’ve now been on two expeditions to Mongolia to visit and photograph Lake Hovsgol National Park, located in the northernmost part of the country. We spent these expeditions making photographs of this area for use by the Mongol Ecology Center in its efforts to protect the lake’s delicate ecosystem. Our first visit was in August of 2015. During this trip, the region was green and lush, with mild to cool temperatures and some rain. The wintertime is a whole different story. Temperatures dip down to 40 below zero Celsius and colder. The landscape becomes starkly beautiful, and ice takes on some amazing characteristics at those temperatures. This article focuses on the winter expedition in February 2017.

Once you get off the few paved roads in Mongolia, a sturdy four-wheel drive vehicle is a must. Toyota Land Cruisers are very popular vehicles due to their toughness and reliability. The Russian-made UAZ-452 4×4 van is ubiquitous in Mongolia due to its relatively low cost and the ability to carry a lot of people and supplies. While these vehicles are tough, they are also cheaply made and prone to break down. The good news is, due to their very basic design and construction, they are fairly easy to fix in the field. Our caravan consisted of two mid-1990s Land Cruisers and a Russian van.

The drive from Ulaanbaatar to Hatgal, located at the southern tip of Lake Hovsgol, is roughly 500 miles and takes about 12 hours in good conditions. In the summer, we took a small plane from Ulaanbaatar to Murun, a short flight that saves about 10 hours of drive time. In the winter, however, the flight is not available. Winter driving is complicated by ice, snow, wind and very cold temperatures, making conditions more dangerous and the therefore the speeds traveled slower.

I am a true California boy, having lived here my whole life. While living in the Sierra Nevada foothills proves “cold” at times, I have never before experienced weather like Mongolia in February, let alone tried to make photographs at those temperatures. Fellow photographer Phil Bond and I did a lot of research to prepare for the trip: boots, gloves, hats, parkas, sleeping bags and of course, camera gear. We had to prepare to keep ourselves (and our gear) warm enough to survive the extreme cold and still make unique photographs.

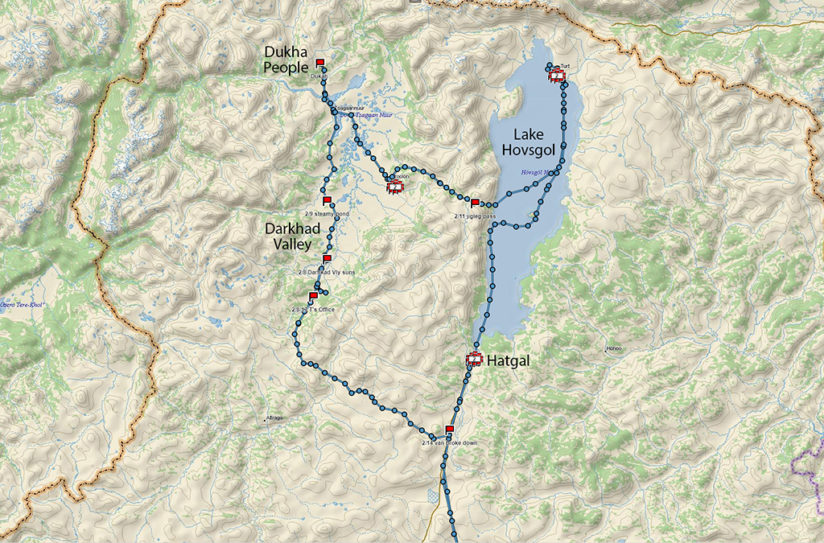

After a late-night arrival in Ulaanbaatar, our trip began before dawn the next day. The long drive to Lake Hovsgol is even longer in the winter. We spent the first night in Hatgal, the largest town near the lake. Here we got to sleep in beds in a warm room. Leaving at dawn the next day, I got my first taste of true cold. I stepped out into the morning air and took a deep breath of -35 degree Celsuis air—it hurt! Air that cold burns your lungs, so we quickly got in the habit of not breathing too deeply. Thus began the journey through the Darkhad Valley.

Our first destination was the winter settlement of a family of the Dukha people, a small community of nomadic reindeer herders. Leaving early from Hatgal, we first drove south to pick up the route that goes northwest to the Darkhad valley. The landscape in the Darkhad valley is breathtaking, with sweeping vistas of mountains and valleys. Between the Darkhad valley and Lake Hovsgol lies the Khoridol Saridag mountain range. We had beautiful sunset views of the mountain range, including the tallest peak in the range, Delgerkhaan Uul, at 3,093 meters.

Upon arrival at the Dukha settlement, we were greeted by an older couple and their two adorable grandchildren. They vacated a pair of their teepees for our use during our short stay. This was the coldest night’s sleep during the trip. The teepees are heated with a small wood stove. When the fire burned out, the inside of the teepee soon became as cold as outside. We were prepared with -30 degree Celsius sleeping bags, but later during the night, one of our drivers came in with an armload of wood and restarted the fire. Another thing to consider when working in these conditions is getting up to relieve yourself in the middle of the night. I’ll just say this is something you learn to do very, very quickly.

The next day I had one of the few issues with my equipment related to the cold weather. I wanted to do an early-morning drone flight over the Dukha settlement, but I couldn’t get the remote for my DJI Mavic Pro to connect with the drone. I took the remote inside the teepee and warmed it over the woodstove. This did the trick, and I was soon flying over the settlement. The older Dukha gentleman who was our host was fascinated by the drone and watched over my shoulder with enthusiasm as I flew over his temporary home.

Leaving our new friends at the Dukha settlement, we headed east through the mountains and on to Lake Hovsgol through the Jigleg Pass. Lake Hovsgol is 136 kilometers long and 36 kilometers wide. It contains roughly 70 percent of Mongolia’s fresh water. The lake freezes in the winter, and the ice is said to be 1 to 2 meters thick. When frozen, the lake becomes a thoroughfare, as it is much easier to take a straight path on the ice than to drive through the mountainous terrain that surrounds the lake.

Looking down at the ice out the window of the Land Cruiser is a little unnerving at first. Yes, the ice is thick and is driven on routinely, but below its frozen veneer is 300 meters of very cold water. Once we stopped the vehicles and got out to make photographs, fear of breaking through the ice disappeared. We were surrounded by incredible patterns and formations in the clear, blue-green ice as far as the eye could see. I could have photographed these patterns for hours.

We spent a couple of nights in the charming town of Hankh, located on the northeastern shore of the lake. We stayed in small, heated cabins and ventured out onto the lake each day to photograph as well as into the mountains that surround Hankh.

Upon leaving Hankh, we drove south the full length of the lake, arriving back at Hatgal, where we had initially arrived a week earlier. We spent the night in Hatgal at park superintendent Turmusukh Jal’s home, then began the long journey back to Ulaaanbaatar very early the next day. About an hour into our long drive, the Russian van broke down. The alternator had gone bad. The drivers spent a couple of hours trying to repair the vehicle with spare parts that were on board, to no avail. The Russian van was able to run on its battery long enough to get us to the town of Murun, where the part was available. While the drivers repaired the van, we were served a delicious lunch at the home of Balgan Naranbold, one of our drivers who lives in Murun.

Due to the delay caused by the breakdown of the Russian van, we spent a night in Erdenet, then completed the journey back to Ulaanbaatar the next day. After eight very cold days with no bathrooms and no showers, we were back in civilization. That first hot shower in a nice hotel in Ulaanbaatar was amazing, but all I could think was that I couldn’t wait to go back to Lake Hovsgol in the winter time.

Expedition To Mongolia: Clothing & Sleeping Bag

When undertaking an expedition in such extreme conditions, first and foremost to consider is your safety. Having the right clothing and using it properly is essential to comfort and survival. There is plenty of information published about how to dress in layers in cold weather and the different materials for the various layers. I wore a Smartwool base layer, a fleece second layer, then either heavy cotton or snow pants on the bottom and a down jacket on the top. I also had a very heavy winter parka that I wore on a couple of the coldest days instead of the down jacket. A balaclava is essential to protect your head and face. I also wore a knit cap made from Mongolian cashmere.

For photographers, one of the most important items is gloves. You need to be able to operate your camera while not having your fingers get so cold that you are in pain. Phil Bond found some great gloves that filled this requirement. They are called Heat 3 Smart Gloves. These gloves were designed for special combat forces in Germany and Austria. They consist of a thin inner glove and a mitten that covers the fingers. It’s easy to get your fingers in and out of the mitten, and the mitten has a pouch for a hand warmer. While our fingers still got cold, it was not to the point of discomfort, and we were able to operate our cameras easily. Speaking of hand and toe warmers, they are essential in these conditions. Be sure to break them open and get them started a good 20 minutes before you think you’ll need them.

Footwear is also an essential item. I found a great boot called the Korkers IceJack. These boots are waterproof, insulated, and have a stainless steel lacing system that is easy to loosen and tighten with gloves on, and they have interchangeable soles. They come with both rubber and studded rubber soles. I also purchased the Icetrac Extreme soles that have carbide-tipped studs, similar to a golf shoe. These were great when we were walking around on the frozen lake. I also got CTFM Toasty Feet insoles for added insulation.

For sleeping, I used a Big Agnes Elk Park 20 sleeping bag (rated to -30 Celsius) and an Exped DownMat 7, which is an inflatable down-insulated sleeping pad. With this setup, I was warm enough even on the very coldest nights.

Camera Equipment

I used three cameras and a drone on this trip. For stills, I used a Sony a7R II and a Canon EOS 5DS R. I shot a documentary film during the trip, and most of the video was shot with a Panasonic LUMIX G85. For aerial stills and video, I used a DJI Mavic Pro drone. All of these cameras performed surprisingly well. None of them ever stopped working or kept me from making pictures. When the Sony was out in the cold for an extended period, first the electronic level would stop working, then the LCD screen would refresh very slowly. It also sounded like the shutter was straining a bit to fire, but it never stopped firing. The Canon never showed any unusual behavior despite being used at temperatures much lower than the manufacturer’s recommendation. I powered all three cameras with an external battery pack that I kept inside my jacket and adapters that plug in to the battery compartment. The XTPower MP-10000 external battery pack only needed recharging a few times during the trip. The only issue with this setup is that the cables for the adapters become very stiff in the extreme cold. I was afraid they might even break, but that never happened.

The Mavic Pro drone also performed very well. My main concern was battery temperature and flight duration. I kept the batteries in warm pockets when not in use. When I launched the Mavic, I would let it hover for a few minutes to generate more heat before I would start the flight. Other than having to warm up the remote one morning over the wood stove, the only issue with the Mavic occurred when I was flying over the frozen lake. I was trying to follow someone who was ice skating, and I couldn’t get the automatic follow function to work. I think the ice was fooling the drone in determining its altitude. I ended up following the skater in manual flight mode, and it’s one of the coolest scenes in the film.

In addition to his photography, Kerik Kouklis is also known for his fine-art, alternative-process prints. Check out his article on making platinum prints from digital files. See more of his work at kerik.com.

The post Expedition To Mongolia appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.