In addition to being a photographer, I own and run a fine-art print lab out of my gallery in Monterey, California. Because of that, I see a lot of files from a lot of different cameras come across my computer screen and through my printers. Recently, I printed a series of images that were fairly large in size. Some were 31×36 inches and others an even larger 36×42 inches. And I was shocked at what I was seeing. Shocked!

To be clear, the camera that took these files that impressed me so wasn’t showing me quality in detail and tonality that I’ve never seen before. In fact, quite the opposite—I’ve seen better and seen it often. The reason I was impressed was because I had never seen detail and tonality come from a device of this type before…not even close.

The tool used was the new iPhone XS Max. Now, I’m not much of a “gear head” in the sense I can’t go on about the differences between the Google Pixel or Samsung Galaxy phones versus the iPhone. I don’t know the device market intimately. Still, I have done a fair share of nature photography with phone cameras and printing from phone files. So I say I was “shocked” at the results because many of the images I printed from the new iPhone were on par in terms of quality with prints that could have been taken by a nice SLR. That’s stunning to me for a dang phone.

After seeing the results, and without hesitation, I called the editor of Outdoor Photographer and pitched the idea for this article. I felt compelled to talk about what I saw and to take this new tool into the field and experience it as a camera instead of just a thing in my pocket. I was given the green light to move forward, so I left my Nikon behind and went to Yosemite and the Eastern Sierras to get some field experience. Here is some of what I’ve found, along with a few tips in case you, too, get the chance to get out and play with this fun new tool.

Handheld Long Exposure With iPhone XS Max Live Photos

It didn’t take long for me to find my favorite new feature of the new iPhone XS. Its predecessor, the iPhone X, was capable of shooting with a shutter speed of 1/3 sec. But the XS is capable of shooting a full second exposure. This feature is my favorite because I love shooting things with or in motion. Furthermore, I can shoot at this slow shutter speed without using a tripod and just handholding.

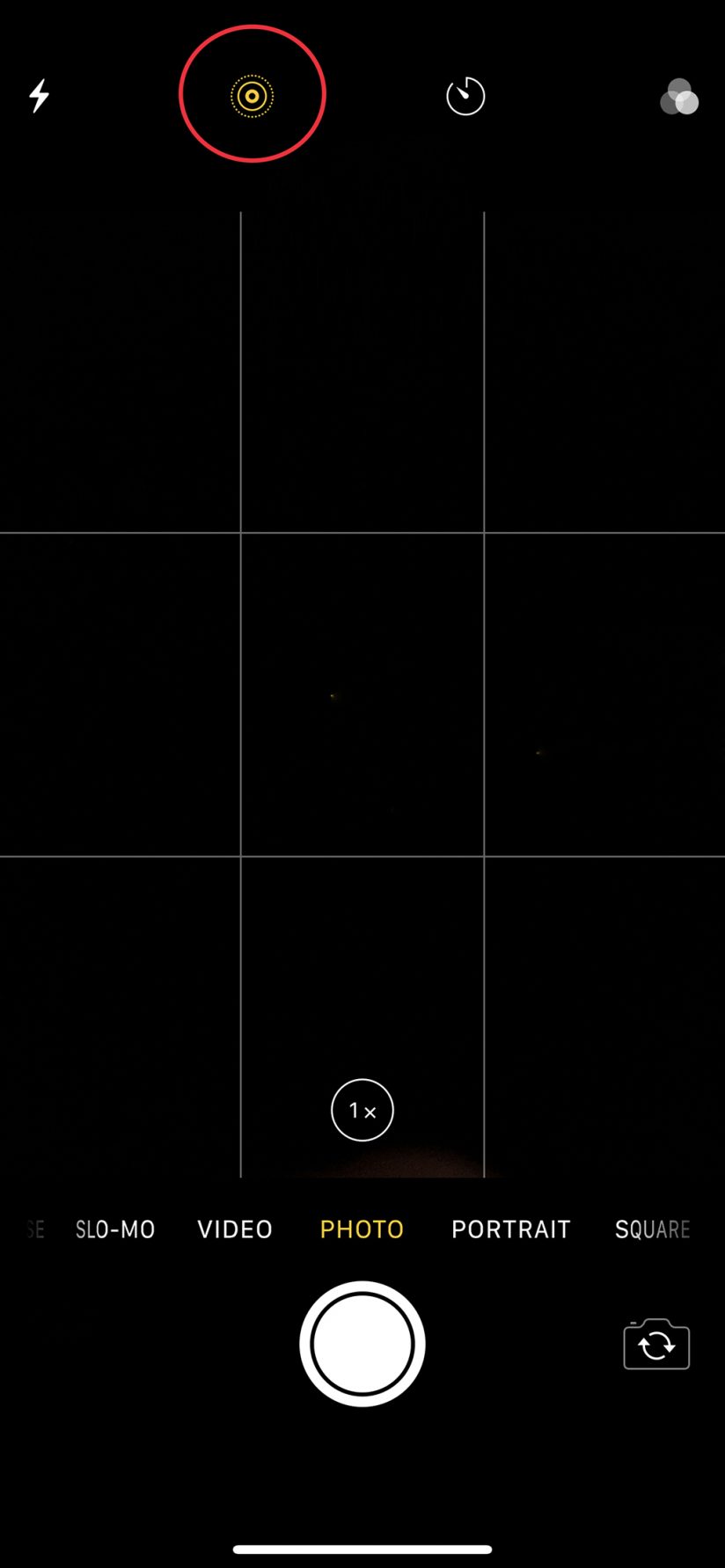

The trick is to shoot the camera while in Live Photos. To turn on Live Photos, hold your camera vertically and point it at a subject, look to the icon that’s second from the left at the top of your screen (shown in Figure 2a). Once it’s on, the iPhone will capture a short video with a key frame set as the picture. After your Live Photos image is captured, visit your image in the Photos app and swipe up to reveal a series of Effects options (Figure 2b).

When you select the Long Exposure option on the right, the elements of the frame that are in motion in the video are computationally blended and separated from parts of the frame that aren’t moving, producing a slow shutter effect. Figure 3 shows a before and after version of when Long Exposure is turned on and off. The results are stunning and terribly fun to play with.

There is a pro and a con to doing this. Handholding and creating long exposures is a non-optical computational effect. Thus, to do it effectively, the iPhone does need to crop into your image slightly. Expect a 15 percent crop while composing. Needless to say, you can handhold this kind of shot and avoid the tripod, but I suggest holding the phone as still as you can. The results will be better.

Smart HDR & Landscapes

HDR (High Dynamic Range) imagery is another form of computational photography that most phones have the capability to do to some degree today. But what the iPhone XS has introduced is something called Smart HDR. Smart HDR mode is the default mode for the new iPhone, and whenever the Camera app is on and working, Smart HDR is also working in the background. With Smart HDR, the iPhone is continuously shooting a four-frame buffer and blending them instantly to bring out shadow detail while preserving detail in your highlights. To put it another way, Smart HDR is computationally, continuously and dramatically broadening the dynamic range of what the iPhone sees and captures.

For the most part, I think this works amazingly well. The thing that’s usually tricky with HDR images in nature, and especially HDR images that are blended automatically, is that there is a very fine line between what looks natural and what looks synthesized. But again, for the most part, Smart HDR is right on the money without any image processing or filtering.

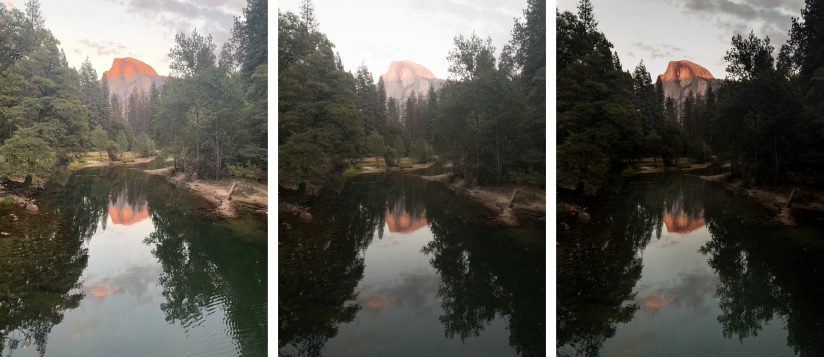

The only times I questioned the results were when I was shooting landscapes with broad ranges between light and shadow. Things just tend to look, well, computational. However, no one says you have to stick to using Smart HDR if it isn’t cutting it. Better yet, let’s all keep in mind that there are third-party apps such as Camera+, VSCO and the Lightroom Mobile app that allow us to actually shoot RAW files with an iPhone. For example, Figure 4 shows you an image I shot looking toward Half Dome in Yosemite as the sun was going down. Notice the tonal differences with the iPhone image shot with Smart HDR on, the RAW image taken with Lightroom Mobile, and finally the RAW image developed with Lightroom Mobile.

Sure, Smart HDR doesn’t always cut it. But we are pushing this technology to the edge when placing it in front of a high-contrast natural landscape. I also think it’s easier to decipher what’s natural light versus synthesized light when looking at natural landscapes. Nonetheless, as I said, Smart HDR is the default, not the requirement. Either way, the results with new phone shooting RAW are quite impressive as well. So there are times to use the Camera’s native app and times to shoot RAW.

RAW Versus Apple’s Camera App

The rules shouldn’t change for us photographers when shooting with an iPhone. We don’t set our cameras to JPEG, we set them to shoot in RAW, and I don’t suggest doing anything different on your phone if you are taking images for which you want to maximize your developmental control, and especially for images that you intend to print. I mostly shot the iPhone RAW in the field. RAW files just have more data offering more tonal range, detail and more latitude to play with shadows and highlights while developing.

Bearing that in mind, there seem to also be pros and cons to shooting RAW with the Lightroom app. For starters, we lose the advantage to shoot one-second handheld images. Lightroom does have the option of manually controlling the shutter, but when slowed down to a full second, it generates a lot of shutter lag, and you’ll need a tripod to keep things steady. On the other hand, if you use a tripod and learn to deal with the lag, you can avoid the 15 percent crop.

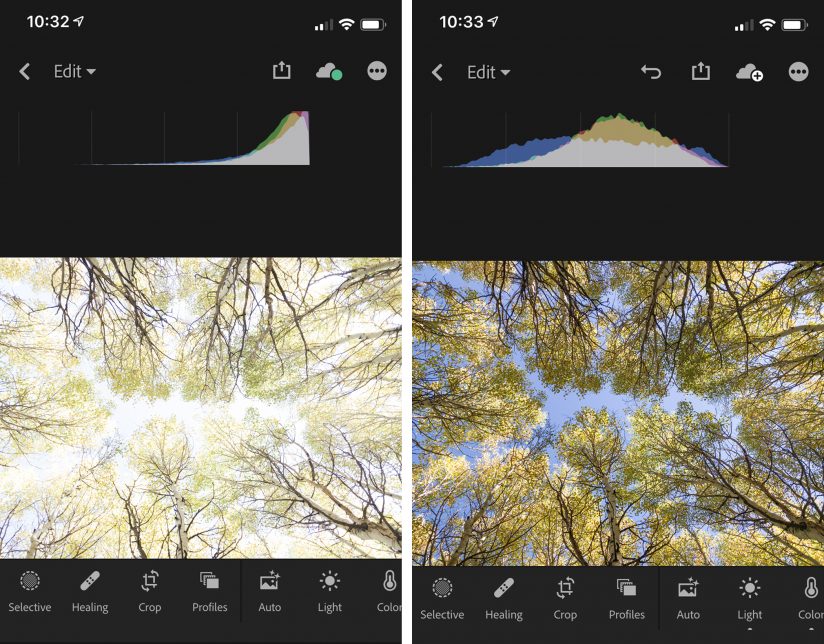

Additionally, I’ve found that when shooting RAW with Lightroom, what you see on the screen while lining up a composition can be vastly different than what you’ve actually captured. I discovered this discrepancy while playing with Exposure Compensation in Lightroom Mobile. While taking a set of photos that needed to be a bit more high key, or brighter in tone, I increased the Exposure Compensation slider. What I saw on my screen looked just the way I wanted. But after I opened the DNG (Adobe’s RAW file format) file itself, I noticed the DNG had clipped highlights and was probably somewhere between 2 to 3 stops overexposed. Figure 5 shows one such RAW file I overexposed accidentally.

So a word of caution: Don’t proof your RAW files by trusting what the iPhone’s showing you as you’re lining up your composition in Lightroom. You need to take a second and actually look at the RAW file after you’ve shot it and look at your histogram to verify your exposure is just the way you want it. Clearly going back and forth between composing your images and accessing your files after they’ve been shot is an extra step that will slow you down. But know you can always go back to the Apple Camera app. You will just sacrifice the larger RAW file size and use Apple’s Camera app instead.

What Else Can The iPhone XS Max Do For Photographers?

Like I said, I’m not a big gear head, but there are reasons I was impressed with what I saw. Interestingly enough, the resolution from the X to the XS hasn’t changed. Yet the XS takes much better images. Here are a couple of reasons.

The new iPhone XS sensor is 30 percent larger than its predecessor—thus the pixels are larger, allowing for better low light capability, a wider ISO range and a broader dynamic range. Still, the megapixels of the sensor have not changed. The X and the XS’s rear-facing cameras produce an image output size of 4032×3024. This implies that the big upgrades we are seeing are a result not of optics but of computation along with the larger sensor.

The iPhone XS has the new A12 Bionic chip, which is a complex CPU that essentially manages the iPhone’s main CPU and GPU. Referred to as the “neural engine,” the A12 chip has increased overall performance by 50 percent, providing much more power for Smart HDR, panoramic stitching, facial mapping and masking, depth-of-field control while in Portrait Mode, and much more. Phil Schiller, the senior vice president of worldwide marketing for Apple, stated in the keynote describing the new iPhone’s camera features that a trillion operations are performed for every photo taken.

Most importantly, I’ve seen the prints (see Figure 6). With sensors and chips as small as they come in the new iPhone, I should not be seeing prints as nice as I’m seeing them. But I am. For a phone, it displays incredible detail, color, sharpness and fine tonal gradations. Computational imagery is the future of photography, like it or not, and the future is certainly approaching fast. For the first time ever, I think the iPhone can be used as a fine-art tool by the masses.

The Continual Democratization Of Photography

Remember the Brownie? Heard of the Brownie? It was a camera that forever changed photography and culture. In February of 1900, the Brownie, the world’s first point-and-shoot camera, was introduced. It was a handheld camera that was made to support the sale of roll film that was also recently invented by Eastman Kodak. The whole thing was genius. They even marketed it to children to help illustrate how easy the camera was to use, and it made photography accessible to the masses. New careers and art forms were built around the Brownie. It was easier, lighter and more affordable than the cameras that came before. Until then, photography was reserved for the well-trained and owners of large-format equipment. The club was more exclusive.

The advent of digital photography also brought about industrial and cultural changes. The instant feedback the technology provided made the craft easier, and today there are more photographers than ever before. Digital cameras brought in another round of “the masses,” just as the Brownie did in its day. What’s better, or worse, depending on your perspective, is that with the additional arrival of image sharing through social media and the internet, we are inundated with imagery. And the frequency of seeing well-crafted imagery is continually growing, democratizing how we experience and practice the art of photography.

To be honest, it’s a bit weird, unexpected and even scary that I’m writing this article. There are always pros and cons to technological advances. I never thought I would be talking about how cool the new iPhone is as a potential fine-art tool for the masses. But here I am. I say it’s weird because I wonder if leaving my Nikon behind and taking only iPhone pics makes me less of a photographer. One of the things setting us photographers apart from the masses with pocket phones is all our expensive gear, our tripods and our interchangeable lenses. Right? And I say scary, because with the new iPhone being such an effective tool, I worry that “the masses” will dilute, with the instant gratification a modern portable device has, what the craftsman spends so much time trying to perfect. I worry that it will make it harder to set oneself apart.

But at the end of the day, my worries don’t matter. Technology is evolving, and phones are getting amazingly better and easier to use. We can’t change that. More importantly, I am a believer that there are things more important than setting ourselves apart. The iPhone, and its ability to create amazing photos, will make things easier, the craft more engaging, which in turn will allow us to put our heavy, expensive gear down just a little bit more. We’ll be lighter, more nimble, more able to play with angles, perspectives and ideas. And the less anyone is encumbered by gear, the more they are able to create. Being creative is more valuable than the expense of any tool. Imagery that’s compelling and thought provoking is never made by the camera; instead, it’s made by photographers with intention and clarity of vision.

The post iPhone XS Max For Nature Photography appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.