Peter Van Noppen organized his folding tables, behind him, the Woonasquatucket River. Peter was the fulcrum for a big day of cleaning, clipping and hauling along this one stretch of the historic river just behind the gloriously restored Rising Sun Mill.

The Woony was once a force powering mills and their machines, then a dirty twisting flow of dioxins, metals and sewage, now a shining example of what man can do to undo what man has done.

The Woony was once a force powering mills and their machines, then a dirty twisting flow of dioxins, metals and sewage, now a shining example of what man can do to undo what man has done.

By 9:00am, despite the strong call of a perfect beach day, 50 volunteers milled amongst the native grasses and mulched river banks, wiggling into waders, queuing up for assignments.

Peter is the Assistant Property Manager for the Providence’s Armory Management Company, which puts him in the right places to see an ebb and flow of water and waste. He’s a young guy ready to get to work, looking over your shoulder, stepping around you to keep things moving. He enlisted the wonderful Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council and the Blackstone River Corridor Inc.’s Bonnie Combs to help organize and promote a day of helping the river get clean. In the shadow of a beautiful bike path and bridge, covering makeshift housing of rough-folded blankets and crushed cigarette packs, cleaning up even this small piece of river was a daunting task.

Every action has an equal and opposite reaction, right? The reverse of hauling filthy garbage out of an unrespected river is the insult of someone having thrown it there in the first place. Who throws a mattress into a river? Old televisions don’t walk themselves past a security post to commit harakiri on a hunk of rusted rebar in three feet of river but they can roll down a steep green bank when Best Buy has new 50” HD’s on a one day sale and laziness overtakes the call of common decency. “The ease of the disease”, wrote Chris Smither, “is more seductive than the cure”.

Every action has an equal and opposite reaction, right? The reverse of hauling filthy garbage out of an unrespected river is the insult of someone having thrown it there in the first place. Who throws a mattress into a river? Old televisions don’t walk themselves past a security post to commit harakiri on a hunk of rusted rebar in three feet of river but they can roll down a steep green bank when Best Buy has new 50” HD’s on a one day sale and laziness overtakes the call of common decency. “The ease of the disease”, wrote Chris Smither, “is more seductive than the cure”.

The river. The Woony.

She shares a man-made history like many others in New England: loved, respected, harnessed, abused, abandoned, revitalized. Thanks to President Clinton, William Jefferson that is, she has been blessed with distinction as a National Heritage River which recognizes her critical role supporting the Industrial Revolution, powering looms, empowering paychecks and carrying away our waste, solid and liquid. From her heart beat in North Smithfield, her 19 miles of flow winds through rural and urban patchworks before first tasting the sea below this cement dam built in 1905. To the south, she combines with  the Moshussuck, amazingly once known as the place where moose watered, to carry single use plastic everything, Red Bull cans and half-smoked plastic tipped cigars until finally freed into the head of Narragansett Bay. Long before we “discovered” the river, she also supported shad, alewives, striped bass and the occasional salmon (the last evidence of a salmon harvest was on the Blackstone back in 1869), all spawning in her upper reaches long before man built the dams, mortared bricks into her fertile soils or discovered the joys of asphalt.

the Moshussuck, amazingly once known as the place where moose watered, to carry single use plastic everything, Red Bull cans and half-smoked plastic tipped cigars until finally freed into the head of Narragansett Bay. Long before we “discovered” the river, she also supported shad, alewives, striped bass and the occasional salmon (the last evidence of a salmon harvest was on the Blackstone back in 1869), all spawning in her upper reaches long before man built the dams, mortared bricks into her fertile soils or discovered the joys of asphalt.

Volunteers removed invasive plants.

Small sunfish with bright green tails swam in circles. Keith Hainley paddled his canoe upstream. A pair of ducks pecked at a bits of plastic wedged against low branches. Bruce Stowers dug glass from a browned cobble dry bottom. A turtle resting adjacent to an Aquafina bottle raced out from his comfy crooked Hankook tire home as debris was moved about. Downstream, Ocean State Tackle’s Dave Henault quickly filled a trash bag with beer cans and bottles. His early observation? “Up here, the beer of choice is Corona, down south it’s Budweiser!” Meanwhile, an endlessly circling Styrofoam clamshell clogged the denil-style fish ladder spillway.

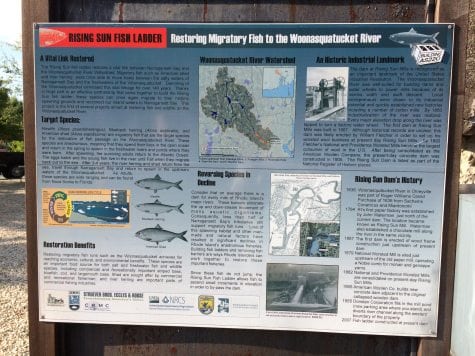

The river benefits from the ladder, built in 2007, to help move anadromous shad and alewives to upper reaches for spawning with a special sluiceway for catadromous eels. WRWC volunteers watch for returning river herring each spring and have counted almost 40,000 in just one year, which really is fantastic. Douglas Watts, in his seminal book, Alewife, wrote that humans have inhabited New England for approximately 9,000 years and for 6,000 years, we have been harvesting river herring. After 6,000 years of taking, we are enjoying a renaissance of return, evidenced by Bruce’s electrofishing here, cataloging dace, catfish, darters, eels and pickerel in addition to buckies and shad.

The river benefits from the ladder, built in 2007, to help move anadromous shad and alewives to upper reaches for spawning with a special sluiceway for catadromous eels. WRWC volunteers watch for returning river herring each spring and have counted almost 40,000 in just one year, which really is fantastic. Douglas Watts, in his seminal book, Alewife, wrote that humans have inhabited New England for approximately 9,000 years and for 6,000 years, we have been harvesting river herring. After 6,000 years of taking, we are enjoying a renaissance of return, evidenced by Bruce’s electrofishing here, cataloging dace, catfish, darters, eels and pickerel in addition to buckies and shad.

Taking a brief break from the arduous task of heaving trash and solely in the name of research, I tossed a copper Mepps just north of a small island in the hopes of getting a strike at a chain pickerel I had seen. Dave Henault offered that some customers have caught four pound bass near there and that shiners would have been a better choice of bait. Always the salesman. As I cast, a volunteer yelled, “See that clump in the middle, it’s actually a shopping cart”. So much for fishing; more trash needed to be hauled away.

Environmental ecologist Garret Hardin once wrote that there is no “away”.

Our trash does not go away, shiny stainless kitchen bins only conceal, 30 yard Dumpsters just transfer. Everything goes somewhere. All these people want is to reclaim a stretch of that “away”.

They won battles of tug-of-war with giant limbs, turned canoes into barges and sweat for hours. By day’s end, there were truckloads of knotweed and rotting lumber, countless tires, bags piled on bags of recyclable glass and plastic, a soggy mattress and that flat screen television.

The WRWC wrote, “In the last 30 years…the river has gone from a valued industrial asset to a neglected natural resource.” In this stretch, six feet deep at most, the water is remarkably clear, a testament to the group’s amazing dedication and persistence to make the river right again. 50 people gathered on the bank are pieces of a great human chain trying to adjust our focus from seeing the Woonasquatucket River as a void to be exploited to a possibility, a potential, a respected resource. Will we see blankets and picnic baskets lining her banks with young folks wistfully gazing into her reflection as others angle for a strike or a meal?

Probably not in our lifetime but the potential is there, sure enough, and organizations like the Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council and people like Peter Van Oppen, David Henault, and Bonnie Combs are working hard to make it happen.

This piece originally appeared in the Southern RI Newspapers. © 2017 todd corayer