Explosions of earth. Skies darkened with ash. Blasts heard over 750 miles away. Who would think that a massive volcanic event would mark the creation of one of Alaska’s greatest wildlife treasures? The biggest eruption of the 20th century turned a mountain top into a caldera and a remote wilderness into Katmai National Park.

Katmai’s Cataclysmic Start

On June 6, 1912, Novarupta blasted into existence. A new fissure in the earth’s surface finally released the building tension of a cluster of volcanoes, exploding with such force that nearby Mt. Katmai—the source of much of the magma during the eruption—collapsed into a caldera at its summit. It was the largest volcanic eruption of the century, some 30 times more powerful than even the infamous Mt. St. Helen.

The eruption lasted for 60 hours, with gas and tephra shot miles into the sky. Earthquakes at magnitudes of 6 and 7 were felt for days. The villages of Savonoski, Kaguyak (Douglas), Kukak and Katmai were coated in ash. When the volcano finally settled down, a 40-square-mile area was covered in a 100- to 700-foot deep blanket of ash, rock fragments and other debris.

The ash flow covered rivers and streams, which sent plumes of steam issuing through the hardening ash. The sight of countless fumaroles at the eruption site astounded Robert F. Griggs, who went to explore the area under the National Geographic Society in the years immediately following the eruption, and he gave this new place a name: Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes.

In 1918, six years after this historic event, President Woodrow Wilson dubbed the area a national monument in an effort to protect both the strange valley and the area around it. Over time, with expanded boundaries and increased protections, that monument became a national park, one of the most spectacular in our parks system.

Katmai National Park 100 Years Later

Thanks to decades of stewardship, Katmai National Park is a 4-million-acre protected home for a rich diversity of wildlife, from sea birds to marine mammals to that icon of the Alaskan coast, brown bears. And thanks to decades of growing tourism, centered in no small part around bear viewing, the park’s treasures are on the radar of wildlife enthusiasts and, of course, photographers.

My first sight of Katmai was two months after the 100th anniversary of the Novarupta eruption, as I looked down at the coastline of the park from a four-passenger floatplane. The coastal bays lead up toward snow-covered mountains that positively sing with wild beauty. It was late summer, and my small group of friends was there to photograph coastal brown bears fishing the streams for salmon. Yet in our week of exploring our tiny piece of Katmai, the bears would be just one of many species on which we trained our cameras. Everywhere we turned our gaze, there was something beautiful to photograph.

This year being Katmai’s centennial year as part of the parks system, we celebrate the sheer wonder that is Katmai National Park.

Bring On The Bears

The coastal brown bears are the largest of the brown bears. Males weigh an average of 900 pounds, and some of the larger males can hit a hefty 1,200 pounds. For comparison, the brown bears found farther inland, such as the popular grizzlies of Yellowstone, weigh 200 to 700 pounds. The only brown bears in the world that are larger than those found in Katmai are the giants of Kodiak Island, just south of Katmai.

Between their awe-inspiring size and their famed fishing techniques, the bears are a major draw for visitors hoping to see them charge down a river, slam into the water with a splash and come up with a salmon clenched between their jaws. And there is plenty of opportunity for such a sight. An estimated 2,200 coastal brown bears call Katmai home. It is the largest protected brown bear population in the world.

Brooks Falls, located near Brooks Camp within the park, is the most well-known location for bear viewing. In 1988, Thomas Mangelsen captured the iconic photo of a bear standing at the falls about to bite down on an airborne salmon. In the years since “Catch of the Day” was published, the popularity of the camp has grown, and bear activity hasn’t disappointed. As many as 50 bears at a time can be spotted at the falls during the height of salmon runs. The bear-viewing platforms overlooking the falls and river are hot-ticket locations, drawing thousands upon thousands of tourists each year.

Indeed, the bears have been a primary draw for many over the parks’ existence, including two unlucky (or unwise) souls. The only deaths by bear attack in the park’s history are that of Timothy Treadwell and his girlfriend, Amie Huguenard, who were mauled to death in 2003 at their camp on Kaflia Bay. Their story was made famous in 2005 by the documentary “Grizzly Man.” The area where they camped is called the Grizzly Maze because the shrubs lining the hillside make it difficult if not impossible for bears and people to see each other coming down a path. The decision to camp here, combined with more than a decade of highly risky and law-defying behavior, lead to Treadwell’s ultimate demise.

These two extremes—crowded or dangerous—are not the only options for seeing bears, of course. Those wanting a quieter and less-populated viewing experience can find other lodges or tour groups, or even book a bear guide for a small group or private trip through the park. As long as a visitor maintains bear-savvy behavior, there is far less danger in exploring Katmai’s rugged reaches than Treadwell’s story (or the sheer number of brown bears living in the area) might imply.

Katmai is so much more than a place to see bears. The rich diversity of wildlife species is especially apparent along the coast, where an abundance of birds, marine mammals and a wide range of habitats will fill hard drive after hard drive with unique images.

Wonderful Wildlife Of Katmai National Park

When taking a break from bear-watching, photographers can turn their cameras toward the water for shots of the undeniably cute and charismatic northern sea otter, a subspecies of sea otter unique to the northern latitudes.

Sea otters have bounced back after being hunted to near extinction during the fur-trade era, and the shores off Katmai National Park are a perfect place to view them. Watching them feed and groom is a delight, especially when it is a mother caring for her pup. While somewhat skittish, they may pop up near boats and stick around at the surface for photographs.

Other marine mammals spotted off the park’s shores include harbor seals, sea lions and porpoises. Humpback whales can be spotted in the Shelikof Strait.

Birders are sure to check dozens of species off their list during a visit to the park, especially during the spring migration and summer breeding seasons. Horned and tufted puffins raise their chicks on the rocky cliffs of the coast, as do black-legged kittiwakes, common murres and other sea bird species. Harlequin ducks can be found nesting alongside swiftly moving streams and rivers, while loons and grebes nest around the lakes and ponds of the park. Birders can spot everything from great horned owls and boreal owls to redpolls and snow buntings.

And, of course, there is the ever-spectacular bald eagle. Once listed as an endangered species in the United States due to the impacts of habitat destruction and DDT poisoning, the species has become not only a symbol of our nation but also a symbol of environmentalism and species recovery. Bald eagles can be photographed year-round, raising chicks in nests situated in trees and on rock stacks, catching salmon or scavenging along beaches.

Another iconic Alaskan species that all visitors hope to glimpse is the wolf. During my trip to Katmai, we spotted fresh wolf tracks in the sand as we walked the shoreline of Hallo Bay, though not the wolves themselves. The following year, a friend working at a lodge in the park emailed me to say that brown bears and wolves had been feeding off a moose carcass here, and the guests were thrilled with the sightings. You just never know what you’re going to see when you’re there!

Planning Your Visit To Katmai National Park

Brooks Camp is by far the biggest tourist draw, and staying here is certainly an option, especially for photographers who want to try their luck and timing to get a photo of a bear catching a salmon jumping the falls. However, for photographers who would like more elbow room, there are many other options.

Trips with bear guides and photography instructors are available, and booking with them will likely lead to the trip one is truly seeking, including a sense of remoteness and a chance to bask in the vast wild that the park holds.

Many trips by boat alongside photography instructors are available, which allows visitors to see more of the coast, hike on land during the day and sleep with a sense of bear-free security at night. My small group opted for staying at a lodge that allows a maximum of 12 guests at a time and provides a bear guide for our outings.

Your experience is your choice in Katmai National Park, but remember that this is indeed a very wild and remote place, so either wilderness experience or a guide are considered a minimum requirement if you’re crafting a custom trip to the park.

The best time of year for your trip to Katmai depends on what you’d like to see. The park is open all year; however, the height of wildlife activity occurs from late spring to early fall.

For bear watching, coastal brown bears feed on sedges and dig for clams in mudflats during the spring and early summer. In late summer and fall, the salmon are running, and bears can be photographed fishing along streams and rivers.

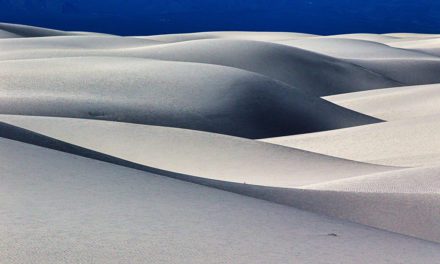

Landscape photographers will find the park thrilling at any time of year. Summers offer longer days to explore the park’s many habitats, from rugged coasts to forests, to tundra, to the incomparable moonscape of Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. Summer also displays an abundance of color and plenty of water flow for shots of waterfalls. Winter, however, offers the chance to photograph the park in a snow-covered season that very few people see with their own eyes.

Plan on encountering rain at any time from spring to fall and bone-chilling cold during winter. That said, temperatures can vary wildly during any season, thanks to the stormy temperament of the Pacific Ocean and Bering Sea. Summers can range from 30 to 80 degrees Fahrenheit, and winters can range from a balmy 50 degrees to a painful 35 degrees below zero. Because of these varying weather conditions, be sure to bring plenty of layers and rain gear for both you and your cameras.

Whatever time of year you visit, and however you choose to adventure, Katmai National Park will take your breath away with its remote beauty and abundance of wildlife. There is no other park like it, and certainly no other park with such an explosive beginning. Any photographer is sure to come home with a broad portfolio of images and a smile-inducing story to go with every single one of them.

See more of Jaymi Heimbuch’s work at jaymiheimbuch.com.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Alaskan Legacy

How Robert Glenn Ketchum became a leading advocate for the preservation of Southwest Alaska’s ecosystems and economies. Read now.

The post Katmai For Wildlife appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.