Just when you think things are back to normal in the woods, you hear of a wildlife issue like the Maine Ghost Moose, and it not only scares you but also breaks your heart. Since Maine is the home to the largest moose population in the lower 48 states, you may think that it is just another issue of nature taking its course.

But it is much worse than that.

As hunters and outdoorspeople, we’re keen on knowing and understanding the details of anything related to wildlife, especially game animals. Maine moose hunting fits among those noteworthy notions, but the tick population has another idea. It’s not bad enough that little blood-sucking creatures try to attach themselves to every mammal out there, but in places like Maine, they’ve become a serious issue for wild moose.

And, according to a report from MainePublic.org, there isn’t much we’re able to do about it.

What is a Ghost Moose?

Vimeo/Maine Public

Winter ticks (also known as moose ticks) have plagued Maine, New Hampshire, Minnesota, and parts of southern Canada for a long time. The issue has worsened as warmer winter temperatures keep ticks feeding and thriving long into the season when historically they would begin dying out. And it’s now killing some 90 percent of the moose calves being tracked by biologists.

According to the report, “It’s not uncommon for biologists or hunters to find moose infested with 40,000, 75,000 or even 90,000 ticks.” That number is hard enough to wrap our heads around. But remember, nearly 90 percent of the calves that the scientists tagged and tracked in 2021 died due to tick infestation.

Many adult bulls and cows can survive such a massive tick load on their bodies, but 60 out of 70 calves tracked did not. With all this in mind, researchers have determined an obvious fact-some of the infested moose rub themselves virtually bald to remove ticks. Thus, the awful phenomenon is known as the “ghost moose.”

Ticks Ravage Moose Population Densities

ChrisBoswell via Getty Images

Decades ago in the Pine Tree State, clear-cutting of the valuable commercial forests had a fantastic effect on moose populations: they thrived and expanded. With the regular and overseen harvests of timber, prime moose habitat was created, which caused a surge in moose numbers that many, including hunters, would think a positive thing.

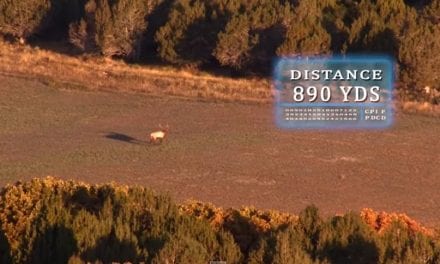

In parts of northern New Hampshire and especially north-central Maine, moose populations haven’t just risen but are considered high density. As you may have seen in the above video, winter ticks not only “quest” for moose, but they do it en masse in incredible numbers so that one encounter can infest a moose with thousands of ticks at once.

Lee Kantar, a lead biologist with the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife (IF&W), said, “You look at one data sheet after another of what we found in the woods on these moose, and it’s the same profile every time: it is winter tick.”

Henry Jones, lead moose biologist of the New Hampshire’s Fish & Game Department, added more about the moose numbers,.”So essentially you had this species, moose, that came in and found all of this food, no predator, their population exploded. Now it is coming back down. Winter ticks act as a system predator, and they are enhanced by the shifting climate, by the warming climate,” he said.

Moose Ticks Hurt Cows & Calves, Too

Maine moose challenged by an increasing tick population due to climate change from Maine Public Video Production on Vimeo.

As Maine Public shared, “Winter ticks are also leading to fewer moose cows carrying pregnancies to full term in Maine and other parts of northern New England.” In 2014, biologists captured a young, healthy cow and dubbed her Moose Number 59, who proceeded to live out her life in the Moosewood Lake area for the next eight years. One day, an antler shed hunter discovered her carcass, identifying her by her ear tag: Number 59.

After getting a call from the shed hunter, biologists, including Kantar, made it out to the scene to do an autopsy on the freshly deceased cow. Before finally succumbing to death, Number 59 might have had as many as 50,000 to 90,000 ticks feeding on her, with many still attached to her carcass.

She was described as having bony hips and massive patches of missing hair-putting Number 59 directly in the Ghost Moose category. What’s worse, she was carrying a calf. Kantar stated that Number 59 was probably within two to three weeks of giving birth. But the calf was still very small for that time in its gestation-12 pounds and roughly two-feet long.

Even if she had survived, the severely malnourished calf would have likely perished, especially since the cow was nearly devoid of any fat reserves. Her organs were almost entirely white, indicating a level of anemia rarely seen in wild animals. And all of this is due to the thousands of parasitic ticks feeding on her all that time. One could say that she died of blood loss without ever bleeding.

What Ticks Mean For Moose Hunting in Maine

RichardSeeley via Getty Images

Interestingly enough, the IF&W has considered what reducing the moose population in high-density areas might do to reduce the infestation. The thinking is that cutting the moose numbers down can make them separate more to the point where these little blood-sucking creatures will have a more difficult time finding a host, especially in the areas where the collared calves were studied.

In this way, they are dividing a 2,000-square-mile wildlife management unit that stretches from the border with Quebec to the western boundary of Baxter State Park. More hunting tags are now allowed in one half of the unit, while in the other half, hunting is still available for moose, but at original levels.

Winter ticks, moose ticks, or whatever you prefer to call them represent a plague for resident moose in Maine. Here’s hoping that wildlife biologists can find a solution soon.

Please check out my book “The Hunter’s Way” from HarperCollins. Be sure to follow my webpage, or on Facebook and YouTube.

READ MORE: THE TICK APP: THE APP THAT TRACKS TICKS

The post Maine Has a Ghost Moose Problem and Seemingly No Solution appeared first on Wide Open Spaces.