We absolutely treasure them. We collect them. We investigate their origins. We tell stories of the hunt about them. We give them places of honor on our call lanyards.

But, official waterfowl leg bands are more than just coveted collectibles, more than just “priceless jewelry” to hunters. The information the bands possess is vital to the management of these web footed birds. There are even monetary reward bands. Getting a duck or goose with a reward, or “money” band on it is extra special because they are relatively rare. The purpose of these bands is to provide an incentive when it comes to calculating harvest rates.

Waterfowl band information reported by hunters and finders plays a critical role in the management of ducks and geese. These details give waterfowl biologists and wildlife managers a wealth of useful data for research and management projects. Specifically, individual identification of birds makes possible studies of dispersal and migration, behavior and social structure, lifespan and survival rate, reproductive success and population growth.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Canadian Wildlife Service, bird banding in North America is important for studying the movement, survival and behavior of birds. Some 60 million birds representing hundreds of species have been banded in North America since 1904. Roughly 4 million of these bands have been reported or recovered.

From a further historical perspective, the National Bird Banding Laboratory, which records and furnishes information about where a bird was banded, where it was recovered, and how long it lived, was used to develop the Flyway system that has been used for managing migratory birds since 1950.

Most of today’s leg bands are made of aluminum and vary in size according to waterfowl species. Each band is inscribed with a unique eight- or nine-digit number, and the last number of the prefix indicates the band size. On average about 350,000 waterfowl are leg banded each year, and around 85,000 are recovered and reported.

The aluminum leg band is only one of the many types of bands that are currently used to mark waterfowl in North America. Neck collars, nasal markers, colored leg bands, web tags, patagial markers and radio/GPS trackers are other types of bands used to mark birds.

Statistics from banded birds are used in monitoring populations, setting hunting seasons/regulations (adaptive management), restoring endangered species and biodiversity, studying the effects of contaminants, and addressing such issues as Avian influenza, bird hazards, and crop damage. Models have been developed that utilize banding and recovery data to predict the impacts of harvest and other take, as well as develop an understanding of environmental factors that drive migratory bird populations.

Results from this modeling and other banding studies continue to support large-scale national and international bird conservation programs such as the North American Waterfowl Management Plan, Partners in Flight and Wetlands for the Americas.

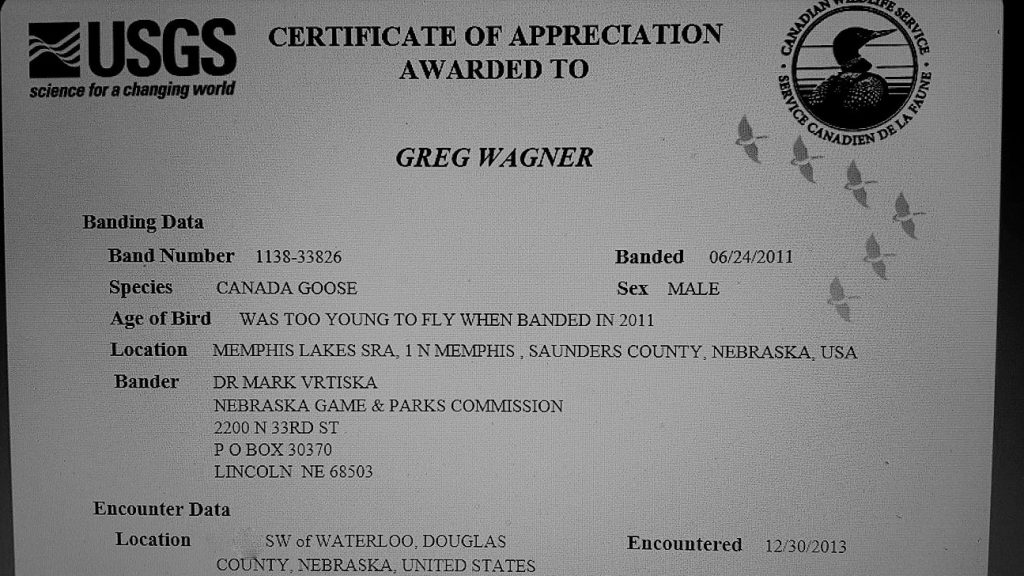

On the state level, Dr. Mark Vrtiska, Waterfowl Program Manager for the Game and Parks Commission, says the biggest bit of information Nebraska receives from bird banding reports is survival rates. Collectively, he emphasizes, those band reports indicate population levels and trends of various waterfowl species.

However waterfowl hunters do not necessarily think about all of those things after shooting a banded bird. They’re really concerned with the true tale the band holds: where and when the duck or goose was banded, how old the bird is, whether it is a male or female, and how far it journeyed before it was harvested.

Sometimes, the information you receive after reporting a band isn’t that dramatic.

A few years ago, I shot a banded Canada goose from a field spread in western Douglas County during Nebraska’s fall/winter dark goose hunting season in its East management unit, only to find out that the male bird had scarcely traveled about 15 miles from where it was banded. It didn’t make for a compelling account, but the data was still quite important, as it illustrated the prevalence of local Canada geese amid the many migrants flying through the area.

On the other hand, some bands tell long distance stories. Take, for instance, waterfowl hunter Weston Cooper’s recently harvested Canada goose. Cooper, from Omaha, shot a Canada goose in southeastern Nebraska on Sunday, January 14th of this year. The bird, had not one, but two leg bands attached (one was a rivet band). This was a female bird banded on July 14th of 2017 in south-central Manitoba, Canada!

Managing a complex and mobile resource requires information on breeding and wintering distribution, behavior, migratory routes, survival and reproduction. Wildlife biologists gather this information by placing uniquely numbered bands on many species of birds and rely on the reporting of bands by the public, but most notably hunters. Incredible insight into the life of that particular bird is gathered.

The value of banding data cannot be underestimated and is only fully realized when band numbers are reported to the Bird Banding Laboratory!

So remember, if you have harvested or found a banded bird, please report it, at: www.reportband.gov You will need the band number, or numbers, if the bird has more than one band. You will also need to know exactly where, when and how you recovered the bird. Your contact information will be requested. Staff at the North American Bird Banding Program’s Bird Banding Laboratory at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Laurel, Maryland will send you a certificate of appreciation that includes information about the sex, age and species of the bird, and where and when it was banded.

By the way, you get to keep the band!

Now, don’t you think that it’s more than just jewelry!

Interesting Fact: Canada geese are banded far more often than other goose species, with more than 2.8 million banded since 1914.

The post More Than Just Jewelry appeared first on NEBRASKALand Magazine.