Enlarge

By Gerry Steinauer, Botanist

Spore-producing ferns are ancient plants, first appearing in fossil records about 360 million years ago, a time when amphibians were venturing out of the oceans to become the first land vertebrates. For tens of millions of years thereafter, the climate was extremely hot and humid and ferns flourished in the Earth’s expansive swamps, some towering to tree height.

Although the flowering and seed-producing angiosperms, such as deciduous trees, grasses and wildflowers, eventually came to dominate the Earth’s flora, ferns continued to fill vital ecological roles. Sixty-six million years ago, for instance, when a massive asteroid slammed into Earth causing a giant explosion, ravaging fires and general cataclysm, as well as extinction of the dinosaurs and three-quarters of all other life, ferns, spreading from refuges via their wind-blown spores, were the first plants to recolonize the barren land and begin Earth’s healing.

Today, there are about 12,000 fern species worldwide, ranging from tree ferns in the tropics to the feathery-leaved ferns often used as ornamentals, to small floating ferns in Nebraska’s playa marshes.

Nebraska Ferns

Of Nebraska’s roughly 1,500 known native plant species, only 31 are ferns. Most of these species inhabit the moist, bluff woodlands bordering the Missouri River and its lower tributaries, but other species grow in habitats ranging from dry, rocky cliffs to constantly-saturated spring seeps. Although a few of our state’s ferns are common and widespread, such as the wetland-inhabiting horsetails and scouring-rushes and the coniferous and deciduous woodland-inhabiting fragile fern, most of our ferns are uncommon or rare. The prairie moonwort, for instance, which tops out at a mere 2 inches tall, has been observed from only one woodland which is dominated by bur oak and cedar in the central Niobrara River Valley. Its habitat is common and a survey by a persistent, some might say obsessive, botanist willing to spend hours, if not days, on hands and knees searching the forest floor would possibly find other populations.

Among Nebraska’s rare ferns is the powdery cloak fern, so named because of its white, powdery leaf under surface. In 1895 it was collected from a limestone cliff along Weeping Water Creek in Cass County and never seen again. Perhaps, it was extirpated by limestone mining in the area. The nearest populations of this plant are in eastern Kansas where it also grows on limestone.

In 1893, the famous botanist P.A. Rydberg chanced upon the crested wood fern in a Sandhills marsh on the upper Dismal River. Botanists have never again found this plant in our state. Could it still be hiding out in the vastness of the Sandhills awaiting rediscovery? The nearest populations of this marsh and moist woodland fern are in eastern Iowa and southeast North Dakota

Few fern species grow in the relatively dry, upland prairie, by far our state’s most abundant native habitat. Among these are smooth scouring rush, which ventures out from wet meadows onto sandy prairie flats and low slopes. In 1999, while morel mushroom hunting in Pawnee County, I discovered the state’s first and only known population of the Engelmann’s adder tongue, so named for the serpent’s tongue shape of its spore-producing leaf. This diminutive fern was growing in and around a plum thicket in tallgrass prairie.

Where are the Seeds?

Like other ancient plants, ferns reproduce through microscopic spores. Early botanists, who had no knowledge of spores, were baffled as to how ferns reproduced. “Where are the seeds?” they pondered.

In medieval Europe, herbalists concluded the seeds must be invisible. Better yet, they bestowed invisibility upon those who possessed them, a god-send for the superstitious, and perhaps not-so-wise thieves and other doers of mischief. Finding the seed usually involved magic and roaming the woods at midnight, sometimes barefooted. If one failed in this adventure, it was often because fairies, goblins or demons had, at the last second, snatched the seed from the seeker’s grasp.

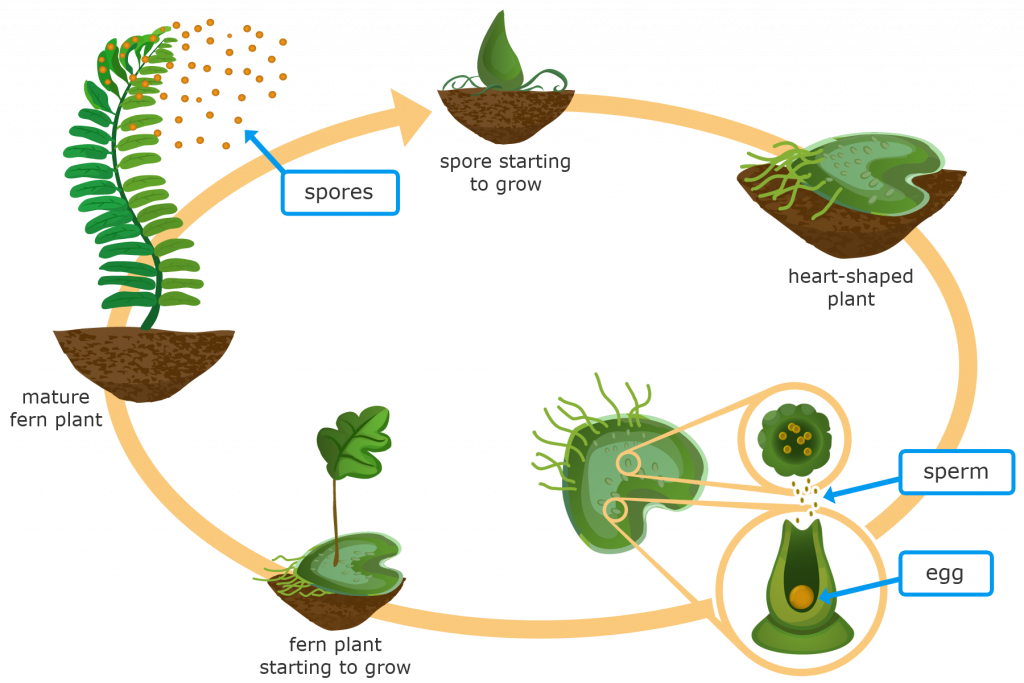

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, botanists, using the newly-invented microscope, unwrapped this fern mystery, finding “they had no seeds” and that their young arose from the “fern dust” that fell from the bumps on the underside of their leaves. Decades later, the dust was discovered to be spores, and the fern life cycle was finally understood. To this day, the complicated life cycle, quite different from that of flowering plants, still confounds botany students and leaves them asking, “Why didn’t I major in psychology?”

The Fern Life Cycle

Wind-blown Spores

Extremely light, fern spores can be blown great distances by wind. They have been found high in the atmosphere where they survive extreme cold and intense ultraviolet radiation. At such altitudes, air currents could carry spores hundreds, if not thousands, of miles.

Recently, three colonies of the never-before-seen-in-our-state cutleaf grape fern have been discovered: two in the woods at Indian Cave Park and one 40 miles to the north near Nebraska City. For more than a century, could botanists have overlooked this plant in Nebraska, or are the colonies of recent origin, their spores wind-blown from populations in northeastern Kansas? In recent decades, the ebony spleenwort also appears to have migrated into southeastern Nebraska, also likely from Kansas populations. If these are spore-instigated migrations, why are they occurring now? Could it be due to climate change?

Perplexing Distributions

Sensitive fern and marsh fern, both found in wetlands in the Sandhills and spring seeps in eastern Nebraska, and several other mostly woodland ferns have perplexing distributions. They grow in eastern North America and eastern Asia and nowhere else. Why? The answer to this mystery lies deep in geological time.

During the early Tertiary Period, 54 to 38 million years ago, the Earth’s climate was much warmer than today, allowing deciduous forests to span the globe at high, northern latitudes. In North America these forests extended into Alaska and Greenland and crossed land bridges westward into Asia and eastward into Europe. The above-mentioned ferns spread throughout this cross-continent forest. As proof, sensitive fern fossils from the time have been found in Greenland, the British Isles and Japan. Later, the Earth’s climate cooled and the forests were forced southward, breaking their continental ties and isolating the ferns in suitable habitats in North America and Asia where they persist to this day.

The World’s Smallest Fern

The eastern mosquito fern grows scattered in central Nebraska’s shallow playa marshes. Along with six other mosquito fern species, they are the world’s smallest fern. The penny-sized plant floats on the water’s surface, drifting to the whims of wave and wind. The branching stems have many small, overlapping leaves and a few thread-like, dangling roots. The name mosquito reflects the belief that the ferns, when dense and covering the water’s surface, keep mosquitoes from breeding.

Mosquito fern spores develop on the leaf’s underside and are released in clumps with three small bladder floats that eventually deteriorate, releasing the spores. Although they have spores, mosquito ferns reproduce mainly by breaking off of the side branches, each fragment growing into a new plant. Waterfowl spread the fragments, enmeshed in mud on their feet, to other wetlands. Highly sensitive to herbicides carried into wetlands by drift and runoff from adjacent crop fields, the plant has declined in Nebraska.

Mosquito fern leaves contain chambers that harbor colonies of the nitrogen-fixing bacteria Anabaena azollae, an attribute that is unique among ferns. This bacteria takes nitrogen gas from the air, which is unusable to plants, and converts it to a nitrate the fern and other plants can use. In China and Vietnam, mosquito ferns have long been used as a green manure in rice paddies, and scientists are developing technologies to expand their use to other areas and crops.

Odd Ferns

With round, hollow, jointed stems and minute leaves that form a ring of blackish teeth atop each joint, the Equisetums, whose common names are horsetail and scouring-rush, look nothing like other ferns. Until recently, botanists thought these spore-producing plants were closely related to ferns, but not true ferns. Recent DNA analysis, however, shows close genetic ties between the two groups: Equisetums are true ferns that diverged form-wise from the other ferns eons ago. Their giant, now extinct ancestors, the Calamites, soared to nearly 70 feet in height.

Four species of Equisetum now inhabit Nebraska. Reaching more than 3 feet in height, common field horsetail, common scouring-rush and smooth scouring-rush are widespread, growing on moist shorelines, floodplain forests and wet meadows. Field horsetail is our only somewhat weedy fern. Spreading via rhizomes, it forms colonies in roadsides and crop fields where it draws the ire of farmers. Known from only a few Sandhills marshes, water horsetail begins growth submerged in up to a foot of water before emerging above the surface.

Many people are familiar with horsetails and scouring rushes because of their jointed stems, and enjoy pulling them apart, joint by joint. Creative kids have been known to string the segments together to create a fern necklace. From a more practical standpoint, their ridged stems are rich in silica, and because they often grow near water, settlers used them to scour pots and pans. The stems also make a great emergency fingernail file.

Equisetum’s spore-producing cones, composed of highly-modified leaves, are born on stem tips. Unique among ferns, their spores have four long, strap-like structures called elaters that coil and uncoil in response to changes in humidity. When dry, the elaters uncoil, creating wind resistance which helps the spore stay aloft. When the humidity rises, such as during fog or after rains, the elaters coil around the spore and it drops to the ground, hopefully onto moist soil suitable for germination.

A New Fern?

Recently, an ecologist sent me a photo of a fern he encountered last summer in oak woods at Rock Glen Wildlife Management Area in Jefferson County. Although the photo is inconclusive, the plant appears to be of a species of shield fern never before found in our state. A collection this coming summer might confirm this exciting find. Nebraska’s ferns continue to fascinate. ■

The post Nebraska’s Fascinating Ferns appeared first on Nebraskaland Magazine.