Public land in Texas is unlike any other.

Peruse a map of most any state in the Western US, and you’ll generally see great sweeping patches of territory administered by the Federal Government, generally as a part of the Bureau of Land Management. Places that serve sportsmen and women well as public hunting areas.

The mission of the BLM, according to its website, is to “sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of America’s public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations.” This mandate encompasses a wide range of management and oversight, including the administration of subsurface mineral and hydrocarbon deposits, the maintenance of public grazing lands, and developing and supporting outdoor recreation.

Hikers, campers, anglers, or hunters in the West have almost certainly availed themselves of BLM land at one time or another. In some western states, it’s almost impossible not to use BLM land. Wyoming, according to this compilation of land data from the Natural Resources Council, is nearly 48% federal land, while 80% of Nevada is administered by federal agencies.

But not in Texas.

Texas is the second largest state in the Union with around 268,000 square miles, and less than 1.5% of that land is owned by the Federal Government, almost all in the form of National Parks like Big Bend, National Forest land, wildlife refuges, or Military Bases, with barely any BLM administered land. There are some state parks, but most of the rest is private property. That leaves anyone without private access to hundreds of acres of land at a loss when it comes to hunting opportunities.

This has profound effects on how people in Texas engage with the outdoors, from the availability of undeveloped backwoods camping, to hunting and fishing access, all the way up to the structure of local tourism. This state has excellent whitetail, waterfowl, feral hog, and dove hunting. However, the public areas are often clogged during hunting season simply because public areas are fewer and far between.

Additionally, in most states in the West, extractive industries are permitted and regulated through the BLM; opening up more public hunting lands. This is not the case in Texas, where the Railroad Commission of Texas is the agency through which companies gain access to the subsurface deposits of oil and minerals in the state.

How did this uniquely Texan condition, a wide-open western state with relatively little public-owned land, come to be? In a word: History.

Most people are familiar with the general structure of Texas history. It used to be a part of Mexico, then there was some fightin’ and some wranglin’, and then it became a sovereign Republic for nearly a decade before getting annexed by the US in 1846. However, in among all that is a fascinating history of land use and governmental oversight that has largely defined the Texas we know today.

The immediate aftermath of the Texas rebellion and independence from Mexico is the key to understanding modern Texas’s sparse federal land. It is important to recognize that the rebellion of largely Anglo settlers in the Republic of Mexico’s northern frontier was predicated mostly on attempts by the Mexican government to restrict American immigration and settlement. Initially, Mexico had welcomed American immigrants, establishing generous grants and land pricing in an attempt to encourage settlement in its northern borders. However, relationships between Mexico and its American immigrants soured over the issue of slavery.

Since the 1820s, Mexico had been introducing restrictions on slavery, eventually outlawing the brutal practice entirely in 1829. However, governmental censuses and reports from Texas indicated that the orders had been largely ignored, and that many of the American settlers still owned slaves. In response, the Mexican government outlawed American immigration into Mexico in 1830, leading to the rebellion and eventual freedom from Mexico in 1836.

Most settlers in Texas had hoped to be quickly annexed by the U.S. following the rebellion. If they had, it is likely that Texas would have seen the majority of its land appropriated by the federal government in a manner similar to other Western territories at the time. However, the issue of slavery again resulted in trouble for Texas.

The 1830s were a contentious time in American politics, with the government attempting to maintain a delicate balance between slave holding states in the South and free states in the North. Continued western expansion was a threat to this balance, and the Texas bid for annexation was largely defeated due to fear that the admission of a large slave holding state in the West would upset the compromises already in place in the Union. Texas, unable to enter the Union, became an independent Republic.

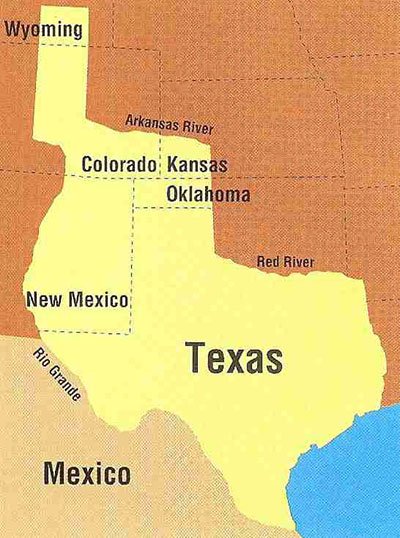

The Republic of Texas’ borders had an outline very different from that of modern Texas. Its eastern boundary was largely similar, though it’s southern boundary was in some dispute with Mexico, who refused to recognize Texas’ independence. Its western and northern borders, however, stretched out to encompass Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico.

The majority of the Republic was unsettled, and as such, much of the land was owned by the new Republic.

The Republic attempted to entice new settlers with grant programs and relatively cheap land costs, although the uncertainty of the Republic’s future, continued wars with Native Americans, and the ever present threat of war with Mexico greatly reduced immigration.

As a result of low immigration, Texas was unable to maintain a sufficient tax base, resulting in the young Republic being saddled with crushing debt.

By the mid-1840s, the political situation regarding Texas had changed. In Washington, William Henry Harrison had died and his vice president, John Tyler, had come to power.

Originally a Whig, Tyler had been expelled from his party for disloyalty, and came into the presidency as an independent. Seeking to gain a solid power base, Tyler had become sympathetic to the slave states and hoped to curry favor with southerners by helping to protect and expand slavery.

More specifically in Texas, Tyler saw the opportunity to endear himself to a large potential voting block by helping them to gain statehood. Indeed, Tyler would come to see the annexation of Texas as a primary goal of his presidency.

A complex series of legal and governmental maneuvers began, with pro-statehood forces in both the Republic of Texas and the US attempting to outmaneuver elements in the American government concerned over the issue of slavery. Eventually, and through some extralegal chicanery, a bill was rammed through congress authorizing the annexation of Texas, skipping over the “territory” phase and directly into statehood on December 29, 1845.

Texas’ wars with Native Americans and skirmishes along the Mexican border meant it owed a lot of money. The US did not want to take on that burden, however, so Texas entered the union with both its debts and lands intact, the first state since the original 13 colonies to do so.

The crushing debt would eventually be cleared as part of the compromise of 1850, which saw Texas ceding its claims over the territories in what would become New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, and Oklahoma in return for $10 million in bonds. However, as a part of the resolution, all of the land within the new, fixed boundary of Texas was the property of the State, rather than the federal government, a situation markedly different from other territories in the West that would eventually become states.

Additionally, the resolution meant that all subsurface deposits, including minerals and (eventually) oil in Texas belonged to the state as well.

Because Texas had kept their claims to public lands, the distribution of land to these settlers was handled through the state, rather than through the Federal Government. Hoping to distribute its land to small-scale settlers rather than land speculators, the State of Texas encouraged family settlement through land grants and other incentives, including low land prices and cheap permitting.

Eventually, by 1900, Texas had disposed of about 216,000,000 acres of public land, placing it into private ownership.

Most western states were originally federally administered territories before achieving statehood; as such their public lands were largely organized and maintained by federal agencies. Texas’s history, first as a rebellious part of Mexico and then as an independent, sovereign Republic, resulted in specific contingencies that explain the paucity of public land in the state.

Because Texas began its life as a part of the United States with ownership over the vast majority of its public lands, it was able to distribute them as it saw fit, creating an environment in the late 1800s amenable to private ownership on a scale unimaginable in any other western US context.

Among other things, this has had a major influence on how people interact with and enjoy the outdoors in Texas, and how outdoor economies have been structured in the State. Accessing hunting and fishing opportunities in particular require different approaches in Texas; in Wyoming, for instance, the Department of the Interior and the BLM maintain numerous fishing turn-outs and trails along creeks and waterways on public land.

Similarly, BLM land in the West echoes with the sound of gunshot and rifle fire in the Fall. Texas’s unique history precludes analogous public access to “wild” landscapes.

As a result, the Lone Star State has fewer access to public wilderness areas, wildlife management areas (WMAs), and recreation areas than most of the surrounding states. Most of those open spaces and previously public areas are now in the hands of private landowners. It’s an important part in understanding the history of the outdoors in this state, and one worth reflecting on the next time you’re outside among nature in Texas.

Products featured on Wide Open Spaces are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our links, we may earn a commission.

NEXT: TIME-LAPSE VIDEO SHOT IN TEXAS SHOWS WHAT HAPPENS AFTER A DEER GOES DOWN [VIDEO]

WATCH

The post Public Land in Texas: A (Very) Brief History appeared first on Wide Open Spaces.