Scientists of yesteryear agree: this crevice in far northwestern Nebraska is in a class by itself.

Enlarge

Story and photos by Justin Haag

Western Nebraska has many landforms labeled canyons. Each contradicts Nebraska’s “flat” stereotype, but a true box canyon – one featuring steep walls on each side with single access for entrance and exit – is a rarity in the state.

One site in the northwest corner of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission’s northwestern-most property fills the bill as such even though it does not carry the name. The crevice known as Devil’s Den, which is geologically carved below the rugged ponderosa pine forest at Gilbert-Baker Wildlife Management Area, is a gem among the many scenic treasures at this public land in beautiful northern Sioux County.

Scenic crannies with steep walls at the head of drainages are not uncommon in the Pine Ridge, but, at more than 500 feet long and as deep as 75 feet in places, this one has to be the most spectacular. Perhaps what makes it most special is its width. At only 10-25 feet wide, there are places along the canyon floor where the sky becomes obscured by overlapping irregularities of the towering walls above.

My first visit to Devil’s Den came in May 2016 by invitation of Wayne and Janece Mollhoff of Ashland. Wayne, one of the state’s most ardent birdwatchers, had stumbled on to the den on a previous visit to the Pine Ridge and considered it worthy for a Nebraskaland photographer to see.

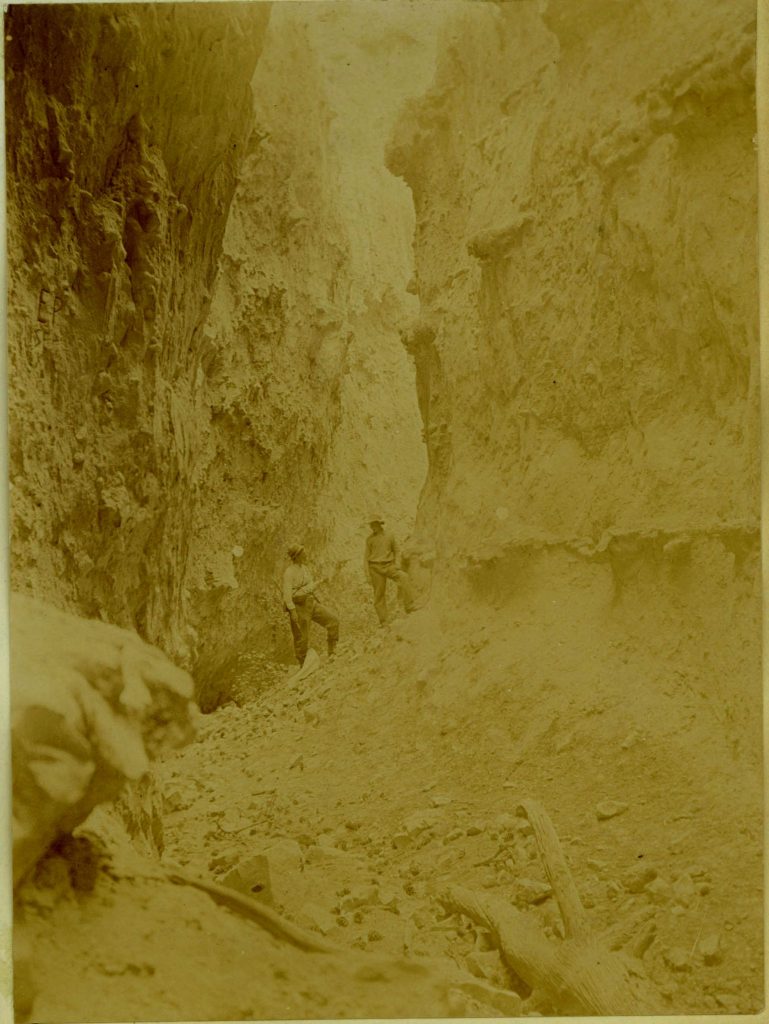

Upon meeting at the Gilbert-Baker parking area along Monroe Canyon Road, Wayne handed me a photocopied image of a Nebraska History Magazine cover that featured a photo from a 1911 University of Nebraska expedition to Sioux County.

Later, I reveled in reading the journal from that early 20th century expedition, written with astute comments and splashes of humor by one of the state’s most renowned naturalists, the late Frank Shoemaker. The journal, which chronicles the June 17-July 2 excursion of that year, provides fascinating insight and observations of the natural world at various sites around Sioux County.

The expedition party, which traveled by train from Lincoln to Harrison, consisted of Shoemaker and six others, including Dr. Robert Wolcott, a zoologist at the University of Nebraska who specialized in ecology and collected beetles, butterflies, myriopods, reptiles and mites.

Despite all of the notable landforms the team encountered during its journey, Shoemaker described Devil’s Den “in a class by itself as regards the geological phenomena of this region.” Knowing that Wayne Mollhoff had observed a lot of Pine Ridge country in his pursuit of species such as white-throated swifts and northern saw-whet owls, my excitement to witness a scene he determined to be special was heightened.

From the parking lot, my then 13-year-old son Sawyer and I set out with the Mollhoffs on the 1.65-mile hike – which seemed 10 times farther than that over the rugged terrain – to the chasm featured in the photograph. After all the ups and downs, the elevation at the ridge above the chasm peaks at 4,900 feet, about 450 feet higher than our starting point.

After making our way down the steep grade and entering the mouth of the crevice, we became awestruck with each step. Our spring visit came 38,315 days after Shoemaker, Wolcott and their guide, Sioux County rancher Noel Priddy, visited the site in late June. Wayne was right – it’s a place a Nebraskaland photographer should see.

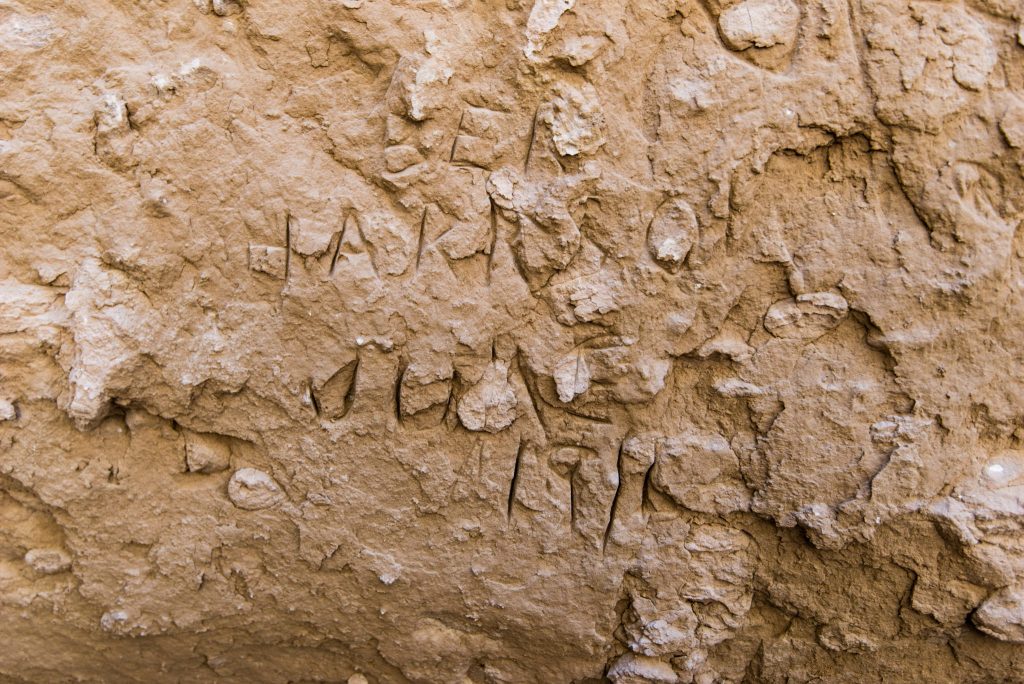

Despite that lengthy span of time, the canyon looked similar to the black and white photo from more than a century ago. Yes, the floor had surely risen a little with eroded sediment from soil and sandstone above, but the canyon retained the same charm. Some fraction of the sediment was surely produced from dozens of carvings along the wall that mark decades of visitors to the remote canyon.

The lush vegetation at the mouth of the chasm gradually gave way to a more barren scene with few signs of plants or animals – except mountain lion tracks that certainly caught our attention. Shoemaker’s journal noted nesting sites of Krider’s hawk (a morph of the red-tailed hawk) and great horned owl in the canyon, but we noticed no such activity. A large rotting log propped on the wall along one of the most narrow parts of the canyon begs wondering how it fell and how long it has been there.

After Wayne surmised the exact spot Shoemaker’s photo was taken, we attempted to restage the scene with him and Janece posing as models. A stubborn shaft of sunlight made its way straight to the bottom of the canyon at the photo site, however, almost as curiously as that rotting log did years before. It created too much of a contrast to overcome by flash. Instead of waiting for the sun to become more agreeable to our efforts, we decided to hike back to the vehicles and perhaps return another day.

Our second effort in May 2018, when the Mollhoffs were visiting the area for the annual meeting of the Nebraska Ornithologists Union, proved more successful. With sunlight cooperating, we did our best to match the focal length, composition and poses in the original photo. The 1911 research party surely would have enjoyed using the Nikon DSLR cameras with the wide range of zoom lenses I was carrying, but nonetheless seemed impressed by the capabilities of its 5×7 long focus box with a Goerz double-anastigmat lens and folding “pocket” Kodak they brought to the region.

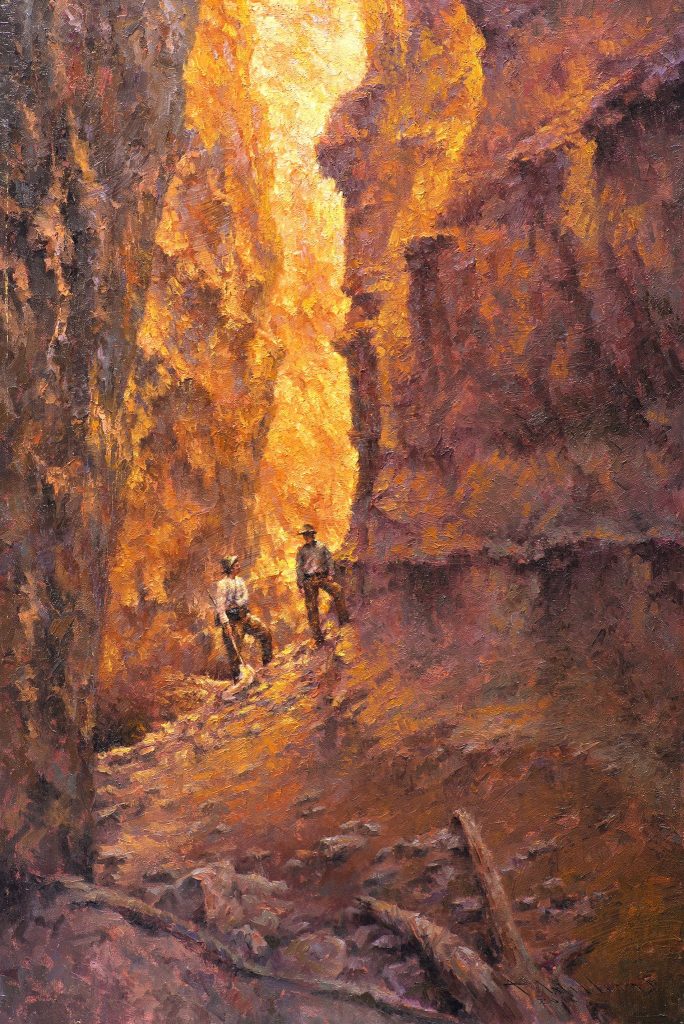

Shoemaker’s classic photo gained publicity in 2017 when a series of paintings with scenes from each county was released by artist Todd A. Williams. To represent Sioux County, Williams, too, recreated the photo.

Other than that, I have not noticed much mention of Devil’s Den. It is not noted on any maps, and I have found only one mention of it in our Nebraskaland archives. A July 1966 story by Richard Williams of Crawford told the tale of how he and another high school student rappelled to the bottom of the crevice at one of its most sheer points, much to the chagrin of the local game warden.

Fortunately, the adventure ended without incident because Richard Williams later became the first American Indian student to earn a degree from the University of Nebraska. Now retired as president and chief executive officer of the American Indian College Fund, he has received a long list of commendations for his work promoting civil rights for Native Americans.

Perhaps someday Devil’s Den will become a popular tourist destination. Similar to many remote, pristine sites in the Pine Ridge, area residents scoff at journalists who provide detailed locations for fear it will be loved to death by too much visitation. Still today, Devil’s Den is not marked by any signs and is hard to pinpoint on satellite imagery because of its narrow outline from above.

Regardless, go for a hike and enjoy this spectacular country. You will know Devil’s Den if you see it. As Shoemaker wrote, it is in a class by itself. ■

The post The Divine Devil’s Den appeared first on Nebraskaland Magazine.