What does the future hold for nature photographers—their equipment, techniques, approaches, output, influence and access to nature subjects themselves? Here are perspectives from two Outdoor Photographer contributors, long-time columnist and nature photography icon George D. Lepp, and Aaron Baggenstos, award-winning nature and wildlife photographer and photo tour leader.

As photographers, we can make a continuing commitment to conservation. The Sheldrick Wildlife Trust in Kenya is an example of a location where visitors can interact with orphaned wildlife and make a difference through their entrance fees and donations. Supporting such organizations will ensure images like these silhouetted Masai giraffes are possible for many future generations to come. Photo by Aaron Baggenstos.

Kathryn Vincent Lepp: DSLRs replaced film SLRs quicker than we expected. Will the same hold true as better mirrorless cameras are introduced?

George D. Lepp: Back in the early days of my career—I’ve been at it for more than 50 years—new camera bodies came along approximately every seven or eight years, a new lens occasionally, and even new film every now and then. The digital revolution changed all that. Now camera bodies and lenses are upgraded every three to four years, but markets are declining for DSLRs and especially compacts. This suggests that development and production may slow a bit in the near future.

I do expect a wholesale move to mirrorless, but with an emphasis on video, which in my opinion is where the field is moving. The ability to extract high-resolution frames from video captures is, to me, the biggest game changer affecting how we capture and how we produce our still photography.

Aaron Baggenstos: I agree that mirrorless cameras are the future of photography. They are smaller and lighter, offer faster capture rates, and are loaded with innovative features that will appeal to both professionals and amateurs. Competition among the many camera manufacturers is now fiercer than ever, which will drive continued and exciting rapid innovation. The outcome is that photographers will benefit from new technology and more creative ways to capture images. When Nikon and Canon get to their second-generation full-frame mirrorless and have native-mount telephoto glass, I foresee this to be the leading edge of the masses switching to mirrorless. When more people make the transition, it will then push mirrorless more into the mainstream market.

KVL: With more photographers and pressure on wild places, the nature scene is getting crowded. In what way is your approach to accessing subjects changing?

AB: More photographers in popular natural places means we need to push our creativity and explore new venues for our images to stand out. It’s a reality as common venues for lovers of nature and wildlife are getting more crowded, and the photographer must search harder for an original image.

The way I work around that is I choose to visit iconic places at times when they are less crowded, usually in the shoulder seasons. This allows me to offer more exclusive venues, which means better value to photographers and more meaningful experiences in the field. I’m also traveling to places not many other photographers venture, like India for Bengal tigers, Madagascar for lemurs, and the San Juan Islands of Washington state for orcas.

Olympus’ futuristic feature set allows for hand-held, in-camera focus stacking with flash, delivering greater depth of field for macro shots like the one of this young parson’s chameleon Baggenstos found in the magical yet disappearing jungle of Madagascar. Taken with an Olympus E-M1X and Olympus M.Zuiko Digital ED 60mm f2.8 Macro, this is a five-image stack merged and processed in camera. Photo by Aaron Baggenstos.

My approach to getting photos isn’t necessarily changing, as my focus continues to be to document, tell stories and, through my workshops, inspire and educate others about the alarming rate at which we are losing species. We can do this through a multi-media approach as the future is giving us new tools in video, audio, stills and drones that elevate our perspective and enhance creativity.

GDL: I have many exciting memories of being the first, or among the first, to photograph some of today’s most iconic natural subjects. Now, when I come across throngs of photographers in pursuit of the same photograph, I am darkly reminded of an old Marine Corps warning: “Spread out, or one grenade will get you all.”

I am deeply concerned about the impacts of increasing numbers of humans on our once-wild places and subjects, and I know that access and crowd control are big issues for photographers whose main business is leading tours and teaching others. But because I no longer conduct field workshops, I have greater freedom of movement these days and again find joy in finding new locations and subjects off the beaten path. I love having the time to dedicate myself unobtrusively to a single subject, such as the progression of an eagle nest from year to year, and to develop some expertise and a body of work on the topic or location.

Greater long-lens capabilities are very important in that they enable photographers to maintain a respectful distance from wild subjects. And features such as in-camera focus stacking facilitate the exploration of macro subjects, revealing new worlds in the smallest of flowers or crystals.

Lepp photographed this bald eagle nest from a distance of about 200 feet using a Canon EOS R and Canon EF 600mm f/4L EF 600mm f/4L IS III USM lens with two Canon Extender EF 2x III (2400mm). The image is a single frame from a 4K video; the 1.83x crop factor yields an equivalent 4392mm final angle of view. The frame has been optimized in Photoshop CC and Topaz Sharpen AI. Photo by George D. Lepp.

KVL: Two important technical issues that face photographers are dealing with low light and noise. What innovations, if any, are on the horizon?

GDL: As digital sensors have improved, the problems of low light and noise have been overcome to a large extent. For me, this opens up a number of important photographic techniques. We use higher ISOs not only to compensate for low light but also to enable higher shutter speeds to stop action, smaller apertures for more depth of field, or even both at the same time to achieve maximum sharpness. As an example, I often use 1600 ISO in the middle of a bright day to stop a bird in flight; 1/2000 sec. at ƒ/16 yields an image of exceptional quality.

Post-capture AI (artificial intelligence) processing software completes the circle, eliminating noise while maintaining sharpness. This is a huge deal for those of us with hundreds of thousands of archived images captured on film or early digital sensors because we can bring those images close to current quality standards. These advancements should lead to a new era in photography; when we don’t worry about the mechanical limitations, our creativity knows no limit other than ourselves.

AB: Cutting-edge camera sensor technology is being developed and refined every year. I have seen an incredible increase in how all of my camera bodies perform in low light, even with more megapixels. Also, excitingly, the new full-frame mirrorless mounts have larger openings, allowing for wider aperture lenses, which ultimately let in more light. AI technology and in-camera noise reduction software are better than they have ever been, and they continue to improve at a rapid rate.

KVL: What innovations do you see happening in post-processing of images?

AB: I think more people are becoming less rigid and more creative with post-processing. The days of shunning someone for removing a stick or piece of garbage from an image are in the past, as the boundary between documentary and illustrative photography is blurring. As before, it will be the intended audience that dictates the applied standards for the photographer’s image.

There are a ton of emerging photography companies driving innovation. Gigapixel AI provides the ability to upscale images so we can print and view them bigger and with more detail. Mobile apps offer animations and creative filters to help turn some images from ordinary to extraordinary. Lightroom presets seem to be a growing market.

To create this high-resolution panorama of Kebler Pass, Colorado, Lepp used a 50.6-megapixel Canon EOS 5DS R and Canon EF 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6L IS II USM at 300mm. The image was captured with a Cognisys StackShot 3x in four rows of eight images for a final composited image size of 46,632×16,788 pixels (1.01 GB). Photo by George D. Lepp.

GDL: I agree, but I worry about what post-processing means to the future of nature photography. A photograph once represented undeniable reality; now it is difficult to believe anything, and we need to be using our craft to educate people about the natural world. I have nothing against creating photo illustrations as long as they are obvious and labeled as such, but I am deeply opposed to alterations that misrepresent a subject, such as adding animals if you don’t have enough, or substituting a great sky from Oregon because you didn’t have one as good in Botswana. AI programs are already making alterations and substitutions even easier, but just because you can doesn’t mean you should. As I judge nature photography contests, I’m always alert to possible manipulation of content, but it’s increasingly difficult to detect. A positive alternative is for contests to invite altered-reality submissions in their own category, so that photographers can work creatively without deception. Expect to see more of these categories in the future.

KVL: What about photo archiving, storage and retrieval?

GDL: The future of all of our images is at risk. Rapid transitions in digital formats have rendered ineffective many of the archiving efforts we’ve made in the last 25 years. Can you read the Kodak Image CDs from 25 years ago? Not well, or not at all. Will the current format of your digital images be able to be read in 10 or 20 years? RAW files are continually changing with each new camera series, and early examples from the first digital cameras—it’s only been 20 years—are already not readable.

I’ve been advised that the DNG (Digital Negative format) or TIFF formats have the best chance for future usability because they have been adopted by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). The DNG format was first developed in 2004 by Adobe and has been given to the ISO, as has the TIFF format. Some photographers I know convert their RAW files into DNG 16-bit files when downloading from the camera. The advantage to the TIFF format is that it accommodates embedded layers.

We don’t know what the digital formats in the future will be, so the one sure answer lies in the past—store prints and slides in controlled environments and back them up with digital scans. I only hope we have a true archival method before these originals also fade away.

AB: In the age of digital, one thing doesn’t change, and that is the need to have redundant backups. You never know when natural disaster such as floods and fire can wipe out your stored archives of treasured photos. Hard drives can fail without warning, and dated technology can sometimes prove challenging in retrieving older images. I always back up three times, with at least one copy being stored offsite in case the primary is damaged. The low cost of cloud services also makes the storage of images in the ether zone quite appealing, especially since you can access images from the cloud while on the road.

Solid state drives and USB-C are the biggest innovations I have seen in this sector. They allow us to process and transfer higher-resolution files faster. CFexpress, the card coming with the next generation of cameras, offers lightning speeds that will allow for even higher resolution files and frame rates.

Olympus’ futuristic feature set allows for hand-held, in-camera focus stacking with flash, delivering greater depth of field for macro shots like the one of this young parson’s chameleon Baggenstos found in the magical yet disappearing jungle of Madagascar. Taken with an Olympus E-M1X and Olympus M.Zuiko Digital ED 60mm f2.8 Macro, this is a five-image stack merged and processed in camera. Photo by Aaron Baggenstos.

KVL: How are mobile phones and social media changing the world of photography?

AB: It’s no secret that people are using mobile phone cameras more for photography. Phones now shoot RAW, have three lenses, run mobile versions of Lightroom and give the ability to upload instantly—all features that make them so appealing.

I see this impacting the beginner and mid-level cameras perhaps negatively as their market share will continue to decrease. However, more innovation will happen at the high-end flagship level of cameras, a point you may have to hit to differentiate your images.

I also sense that social media and mobile phones are spurring the growth of concept photography—a more abstract genre and technique that aims to capture ideas, emotions and evoke feelings, and even tell a story or convey a message. There’s no reason we can’t integrate this into images of nature and wildlife, especially with our important messages about conservation.

GDL: The very best camera is the one you have with you, and even for me that sometimes is a smartphone. Phone-based cameras get better with each iteration and produce images of high quality for small-screen purposes. The only thing that keeps them from replacing pro-level DSLRs is the latter’s ability to produce quality for larger production and to use varying optics, such as long telephotos. But already there is talk of 10x zooms and 40-megapixel sensors on smartphones. You think everyone is a photographer now?

For me, the problem is not the simplified camera technology offered by smartphones, or even the proliferation of images—billions per day—that circulate through social media. Rather, it is the absence of gatekeepers, aka editors, in that free-for-all realm; everyone’s image, worthy or not, everyone’s unedited opinion, is out there, and the sheer volume obscures quality and meaningful content and devalues serious photography to a point of worthlessness. For me, this is the most negative and depressing aspect of the present, and future, of photography in general and nature photography in particular.

KVL: In your wildest dreams about the future of photography, where do you see it going in the next decade? What is it going to mean to be a photographer in the future?

GDL: Back on the bright side, I look at the changes in this industry over the past half-century and maintain excitement about the future. With each new development, I am able to solve photographic problems I didn’t even know I had, and that empowers me.

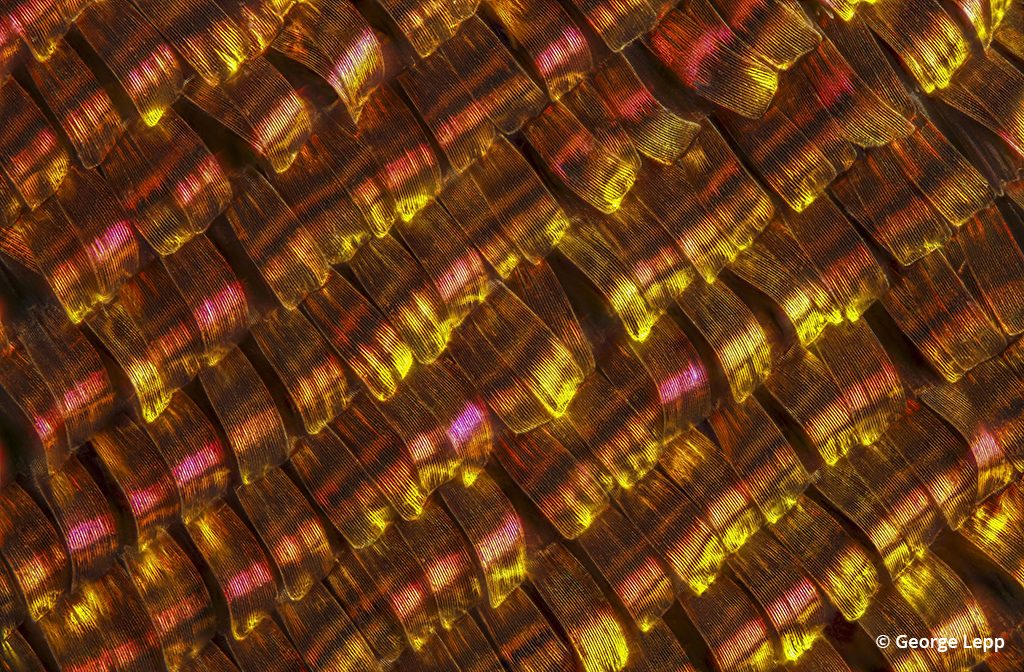

Butterfly wing scales at high magnification. A 20x focus-stacked composite of 32 images captured using cross-polarized light from the Canon Macro Twin Lite MT-24EX. Captured with a Canon EOS R and Canon EF 180mm f/3.5L Macro USM lens with a 20x/0.40 plan microscope objective attached, and a polarizing filter mounted in the Drop-In Filter Mount Adapter EF-EOS R with Drop-In Circular Polarizing Filter. Photo by George D. Lepp.

Nature photography brings people together as they share their experiences visually, and it can do so much good in calling attention to threats to species and environments, not to mention the planet as a whole. We have the tools for capture, and they will only get better. We have many places to present those images, but will they be truly seen?

What will it mean to become an influential photographer in the future? Pretty much what it is today. Produce meaningful work. Live in the “now” of technology. Adapt, learn, adapt again. Be creative and show people things they don’t see on their own every day. Support the good work of others, and receive and share inspiration.

AB: Conservation and sustainability are the major pillars for the future of nature and wildlife photography.

Cameras with extremely high-resolution sensors can now capture a level of detail unimagined before, and software will interpret and process these files in new and creative ways. Unlimited depth of field offers a variable focal point in post-processing. Cameras with higher frame rates are now possible since memory cards are faster than ever, making it possible to push those large-sized image files at lightning speeds. And raw video capture will transform the world of both stills and video, allowing for enhanced color grading and raw stills that you can extract and edit in post.

However, the future of photography is still defined by what makes great photography in the present. That won’t fundamentally change. As acclaimed photographer Irving Penn once said, “A good photograph is one that communicates a fact, touches the heart and leaves the viewer a changed person for having seen it.” This is where the magic of photography happens, with a creative boost from technological innovations that are here today, and some just around the corner. The world of photography continues to be an exciting journey.

GDL: A journey it is. Thanks, Aaron, for proposing this collaboration. I’m not quite ready to pass the torch yet, so I’ll see you out there!

The post The Future of Nature Photography appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.