Have you seen the movie “Glengarry Glen Ross?” It’s a great movie about salesmen and sales culture, and there’s a very memorable line from it. Actor Alec Baldwin makes a cameo to address a room full of burned-out real estate salesmen and set up the plot for the rest of the movie. Baldwin yells at a salesman played by the late Jack Lemmon, who is pouring coffee as Baldwin is trying to make a serious speech. Baldwin scolds him, barking, “Put the coffee down. Coffee is for closers!” Lemmon’s attention, along with that of the rest of the room, is swiftly grabbed, and Baldwin continues by announcing the rules for a new office contest. “First prize is a Cadillac Eldorado … Second prize’s a set of steak knives. Third prize is you’re fired.”

Rewards of coffee or anything else were reserved for the closers, salesmen who could hold their own and took their jobs seriously. A “closer” is a sales term. It refers to the kind of salesman who is skilled in closing the deal, or getting the customer to sign on the dotted line, so to speak. And this brings me to point of this article: Put the tripod down. Tripods are for closers!

Sorry to be so harsh, but it’s necessary, and I do believe such language is for your own good. I’m not just preaching here. This is a demand I put on myself time and time again. The fact is, there are many shoots where I’ve begun by planting my tripod firmly on the ground and played with composition and settings to dial in my exposure. I’d bet you’ve done it, too.

Typically, what follows for me is a realization that composition and settings need to be tweaked, and then tweaked again, and then again. Settings are ultimately changed, tripods are moved, and the saga continues. Plant the tripod slightly to the left or slightly to the right, raise the legs, then lower the legs, and try and try to figure it out as I go. Sometimes figuring it out comes quickly, and sometimes it takes time, but with all the gear it is certainly more cumbersome than it needs to be — that’s a given.

Whatever the case, it’s easy to get caught up in our gear and in our technique, to get lost in settings and dials. We’ve invested in all this stuff, so why not use it, right? I believe gear and technique are crucially important for a photographer; a craftsman must have command of his or her tools. But at the same time, they are tools and aren’t what matters in creating a successful image. Therefore, I’m suggesting we start with what matters when I say, “Put the tripod down.”

The gear and techniques we rely on are rarely, if ever, the foundation for compelling, thought-provoking work. Photographs that stick with an audience have something to say beyond a “That’s a pretty sunset!” response. Assuming that creating meaningful and thoughtful work beyond the snapshot is the goal, I believe the foundation of a truly successful photograph is rooted in a vision, an idea or a voice — equipment is almost incidental.

If I can gain clarity of thought and meaning for an image I want to make, and if I can wield gear and technique in such a way that best expresses that, a rare and magical thing actually happens. The famous French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson once famously said, “It is an illusion that photos are made with the camera … they are made with the eye, heart and head.”

But how does one practice this shift in priority from gear and technique to heart and head? Well, underneath my tongue-in-cheek suggestion to put that tripod down, may I further suggest a workflow where we all look at, study and sketch our scenes before we ever attempt find our spots with a tripod to take an image.

The Art Of Looking And Studying

Starting with experience instead of gear is what matters. One of the key reasons I decided to take up nature photography was so I can stay working outdoors. In fact, when I first got the idea, I didn’t know anything about cameras and had no idea what an aperture was, let alone how to set one. Nature photography provides me with the opportunity to experience nature a deeper way.

With the aid of a camera, we have the opportunity to see more than the average person. While a typical outdoor hiker may stop for a few minutes to gaze at something interesting, like a sunset, I’ll often spend hours on a scene studying the topography, hoping to find its most appealing characteristics and hidden features. I’ll analyze where the light is, where shadows are being cast, and where the clouds are, and try and predict where they are headed as time moves on. I’ll assess high and low angles, which animals are scurrying about, the plant life that is present, and ultimately see and involve myself in a landscape in a way most people never get to do. I try to truly get into the rhythms and pulses of nature. It also makes sense that having a deeper understanding of a thing offers increased potential for interpreting it, for photographing it.

I try my best to begin a shoot by first just looking. My goal is to slowly study what’s around me and get a feel for the scene before I decide how to respond to it. As I study a scene, I ask myself questions. Why have I stopped here, and what’s caught my attention now? I need to know if what grabbed me is a color, a texture, a pattern, a shape, a movement or a stillness; is it the light or the shadows, or is it a mixture? What am I interpreting? I need to know, because without answers I’m literally playing with technique I’ve been taught, read about or copied — nothing personal about that. But once I know the answers, I can determine how I to use my camera to decipher that thing that grabbed me to begin with.

If I know my interest is the color of a beautiful sunset at a beach, I’m not going to take an image that’s all sand and little to no sky. I would know to compose my frame where the color was dominating, and any use of sandy beach, or other available elements that a given landscape might provide, would be used to anchor a scene or give it context, if used at all. In the case of Figure 3, the first image shown is focused in a horizon line with nothing particularly interesting in terms of subject matter or meaning. There are nice colors in the image, but attention is drawn to what’s in focus. But I knew, after more looking, studying, asking questions and self-reflection, that it was the color, and nothing but the color, that compelled me to lift my camera. Where the eye of someone viewing my image landed in the frame was incidental to what I wanted to say. So, in creating the final image, I started playing with slow shutter speeds and panning across the horizon line. The blurred motion removed everything from my frame, leaving only the color and the lines separating the different tones.

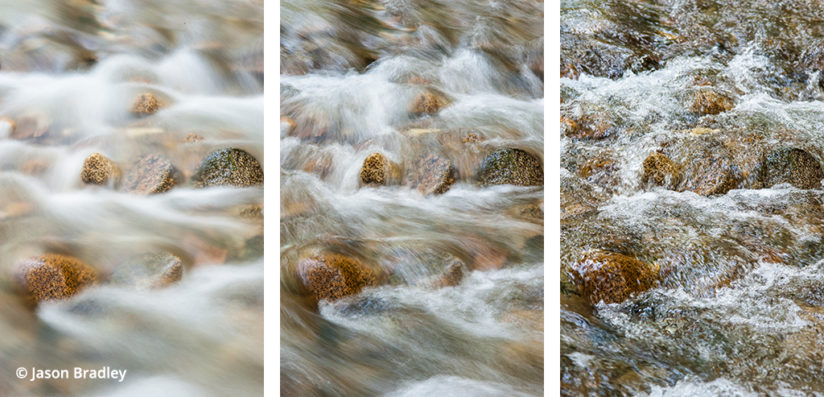

As we shift our priority from gear and technique to heart and head, how and why we use our gear and technique also shifts. Composition becomes a way of either incorporating elements to support our idea or eliminating them if they don’t. Wide or small apertures become compositional choices to control how we either separate foreground from background or bring them together through narrowing or broadening depth-of-field. Shutter speed becomes not just a way to keep things sharp, but also a tool to emphasize movement when using a slow shutter or to accentuate detail when the shutter is set fast (see Figure 4). Telephoto lenses allow me to constrict spatial relationships, while wide-angle lenses amplify them.

My goal is to use gear, camera and settings not so much as a way for creating a good histogram or correct exposure as much as I use them to support a narrative. As we need an architect and a blueprint before using tools build a house, we photographers need clearer ideas before using our tools.

So before picking up your tripod or, better yet, before looking through your viewfinder, look first with your eyes, head and heart. Try asking yourself what it is you’re shooting and why is that you’re shooting it. Determine what your image’s subject and meaning are. Develop your vision for your image first, and then you’ll intuitively know if a tripod is even necessary and what your settings should be.

Sketching

A sketch is a quick and informal rendering of your scene, and will help you determine if what you’re shooting is aligned with what you’re thinking or feeling. It’s a way to proof your idea through your camera. And, truth be told, gaining clarity of subject and narrative doesn’t always magically come to me when I ask myself a series of questions. Sometimes the answers are mysterious and hidden away and need to be coaxed out. Sketching is a great way to find what you’re looking for. But there are some rules to follow while sketching.

First of all, I suggest sketching a scene with little to no regard for the efficiency of your settings, and whether or not you’re creating good exposure or perfect compositions. It doesn’t matter. In fact, I often use my iPhone or a pocket camera, if I remember to bring it. Just know that this is a time that you’re free of your tripod, so you can move around, look through one lens from one angle or perspective, and then look through another lens. Stand up, sit down, lie down, get closer and then move away. Get a feel for the basic elements of your composition to see if there is something there to work with. Your goal is to align what is in your frame to what you’re thinking and feeling. Then and only then are you ready for your tripod and to dial in your camera. Most importantly, if the elements of your frame aren’t coming together, be prepared to adapt by changing your perspective, or even your idea, until they do.

Figure 5, for example, shows a bit of a sketching workflow. My eye was initially captured by a pattern of threading that wove its way in between the fronds of a yucca plant. I first used my Nikon 24-70mm lens and put it inside the plant. The results fell far short of isolating the pattern that caught my eye. So I switched to my 105mm macro lens and opened my aperture to ƒ/2.8 to minimize my depth-of-field, so I could blur out the background, and was much happier with the result.

Here’s a thought for practicing the sketch. Although I’m mostly self-taught as a photographer, I did take in a couple of semesters at Santa Monica City College once upon a time. One assignment that sticks with me to this day was given to me by my instructor, Mr. Fier, in an Intro to Photography course. We were each told to go into the field with one roll of film with 36 frames. Each frame we took on that roll was to be of the same subject, and each frame was to be taken from a different angle. At first this assignment seemed like a cinch, and for the first 10 to 15 frames it was. But after I got through that set of “easy” frames, it quickly became clear that I would have to start using creative parts of my brain to get through the second half of the roll of film. So I began to study my scene and think about all sorts of different ways to see and render what I was shooting. And I tried everything in terms of different perspectives, lenses and techniques, until I started seeing the subject in new and exciting ways. It was a great assignment, as it taught me that if I ever want to make imagery beyond the standard, the easy, the snapshot — if I ever want to make images that are compelling or thought-provoking — I had to stay with something and get to know it intimately. And since virtually all of us shoot digital these days, we don’t have to worry about wasting film as we go. Sketching is a no-brainer.

So, the next time you stroll up to a scene, and before you plant your tripod firmly in front of you, first get familiar with what’s around you. Put that tripod down and study all of the possibilities, see what your scene has to offer you, and seek clarity on what your image’s subject and meaning are through sketching out your ideas. Your gear and your technique almost set themselves when you do — I would gladly bet a set of steak knives on that.

The post Tripods Are For Closers appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.