By Todd Corayer

Special to Outdoor Enthusiast Lifestyle Magazine

Our landscapes are changing quickly. By some reckoning, we asked for it. We pulled a lever for change in Washington and we got it.

The landscape of change became a whole lot larger too. The change people demanded to strengthen some parts of our great country is eroding others, like the environment and our access to it. By the time we stop arguing, resources we need and love may be eviscerated by needs and wants driven by greed and short-sighted investment. These are sociologist Robert Mertonhese’s “unintended consequences.”

Public land. Period.

To better understand consequences which confront and confound us and what’s being done to avoid them, we sat down with Chris Wood, CEO and President of Trout Unlimited, in his Washington D.C. office. Chris leans in when he talks, uses words like “roadless, birthright, amazing, massive and God”, leads a national conservation group and is agreeable to meeting with people who love fishing cold, clean waters and those who might not care so much. We talked climate change, public lands, sinuosity and fishing from a shopping cart.

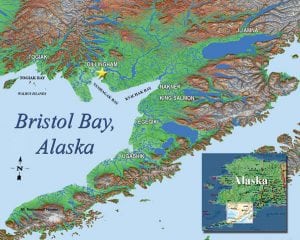

We started with the proposed Pebble Mine because it mirrors other tracts in other states which some wish to exploit and some want to protect. A Canadian corporation has applied to excavate for deposits of gold, molybdenum, silver and copper at the headwaters of Bristol Bay, Alaska. It’s called Pebble because some ore deposits are close to the surface and scattered throughout the landscape, like pebbles, while others are deeper, requiring drilling and shafting.

Map courtesy of Pride of Bristol Bay

“Why should anybody care,” I asked.

“They should care about Bristol Bay because it is the most remarkable salmon fishery in the world,” Chris said.

Our conversation could have ended right there.

“So there are seven rivers that drain into Bristol Bay,” he said. “On two of them, one is called the Kvichak and one’s called the Nushagak… this Canadian mining company, in the headwaters where

those rivers start, is proposing to build the so-called Pebble Mine. The reason they call it the Pebble Mine is that unlike typical veins of ore, they’re not concentrated in one place, they’re spread across the entire landscape. So they’d have to literally develop a massive area, it would be a massive mine, one of the largest mines we’ve ever had, in the headwaters of these two river systems.”

“Let me tell you about these river systems,” he said. “The Nushagak, every year, is one of the top two or three Chinook producers, or King producers, in the world. And the Kvichak, every year, from this one single river, come half of all the world’s wild sockeye salmon. One river. Half of the world’s wild, sockeye salmon. That commercial fishing industry supports 17,000 jobs, it creates $1.4 billion in economic opportunity every year and it will do so in perpetuity, so long as we don’t screw that place up.”

Far off in the woods, right where we need to be.

“And I haven’t mentioned the rainbows.” he continued. “That’s native rainbow habitat. Every year these rainbows, they’re over thirty inches, the size of steel head, move from Lake Iliamna and they follow the salmon into these rivers and feed on their eggs. It’s one of the few places on Earth, with any cast, you better have your A-game on, because you might just hook into a 33″ rainbow trout. It’s crazy”

For perspective, Chris noted that, “You’re talking about a landscape that’s about the size of Ohio and has about six thousand people who live in it. In order to build a mine of that magnitude, they’d have to build a several hundred foot high dam that would be several miles in length. It would be earthen. It’s a highly seismically active area,” he said, referring to the geology, not the current administration. “Just the infrastructure,” he continued, “that they would need, the roads, the pipelines, the energy pants, they would have to literally industrialize what is now an absolutely pristine landscape…”

Public sentiment is clearly opposed to the proposal. According to TU’s Nellie Williams, the EPA’s own threat review showed, “99 percent of all comments were in favor if up-front protections for the Bristol Bay region.” Despite this, the New EPA Administrator is allowing the permitting process to begin.

“Of all the places in the world to put a mine, You could probably have a map of the entire United States, it would be difficult to pick a worse place to put a mine. In fact, I can’t think of a worse place to put a mine.”

Where trout swim and bears walk

TU is not opposed to mining; they have worked closely with mining companies including Kinross and Freeport-McMoRan on issues like water rights, critical elk habitat and building partnerships to clean up abandoned mines.

“We’re equal opportunity conservationists at TU. If you care about trout and salmon, we will work with you,” Chris said.

“But this is one place, we are not only in a ‘No’ but a ‘Hell No’ position as an organization.”

“What does TU do to convince the average person that the value of the salmon is greater than the value of gold?” I asked.

“We always talk about the economic benefits of the fishery,” Chris said, “because that’s something that people intrinsically get. We have spent as a country now, about $13 billion, over the past 20 years, trying to recover salmon in the Columbia River Basin…where we have hundreds of stocks of salmon that have become extirpated and hundreds that are at risk of extinction. And here, in Bristol Bay, we have a fishery that works just as God made it. It is a perfect fishery. And it will stay that way, as I said earlier, into perpetuity, so long as we don’t screw it up.”

In the northeast, think squeteague, cod or northern pink shrimp and you’ll understand his passion to protect.

“There’s a very basic and fundamental choice here,” Chris continued, “do we allow for short-term profit? You know the mine will have played out in twenty years, we’ll have ruined that landscape, we’ll have ruined that fishery, those jobs will go away.” Retaining toxic mine tailings will require building the world’s largest earthen wall, some seven hundred feet tall and several miles long. “This will create a tremendous amount of acid mine drainage, that drainage will have to be treated in perpetuity…that drainage will require perpetual treatment…they’re not going to be able to just button this thing up and walk away,” Chris said, “They’re going to be up there forever. Perpetual is a long time. They will be perpetually treating the waste that’s created by this mine if it’s allowed to go forward.”

“It’s going to stay, right up there at the headwaters of Bristol Bay. ”

I asked what relationship TU has with EPA chief Scott Pruitt.

“We are one of the only organizations that met with him. Early on in his tenure, I wrote to him and asked for a meeting and had a great meeting. I had just testified on Capital Hill in support of some legislation to clean up abandoned mines, which you know is a big problem. Ironically we’re talking about cleaning up billions of dollars worth of abandoned mines while we’re trying to keep one from being built in Bristol Bay.”

“We had a great conversation,” he continued. “I wanted to talk about three things, the first was I wanted to talk about abandoned mines. We had an awesome conversation. He could not have been more receptive,” Chris said. “He promised help, was very interested in finding out what EPA could do to ease liabilities that are associated with abandoned mines.” That’s a big issue out west where land purchases might include such a mine, making landowners and conservation groups who want to help, part of the chain of custody for spoils left behind. “That conversation went great,” he saidm “I mean that’s an easy issue, there’s no constituency for acid mine drainage. Nobody likes yellow rivers.”

Next, they talked about 2015’s Clean Water Rule and EPA’s efforts to largely eliminate inclusion of headwaters and small streams from environmental protection and focus more on larger rivers and navigable waters. “That would basically remove the protection of the Clean Water Act for sixty percent of the stream miles in the US. It’s a ludicrous and radical idea.”

“So it’s for the benefit of business?” I asked.

Chris leaned in and said, “Who it’s not for the benefit of, is anglers. Or the third of Americans who get their drinking water from those river systems. That was a slightly frostier conversation.”

Peace, cold water, trout.

The third topic was Bristol Bay. “That was short. We had a widely divergent set of perspectives. I think his belief is that the process needs to play out, the process needs to be followed and if we follow the process, then the right decision will be made,” Chris said. He spoke of how elected officials can “hide behind the process. When you think about the great conservation achievements in this country, Theodore Roosevelt thinking about creating national monuments and the Grand Canyon and making that a national park. People like Gifford Pinchot, the first Chief of the Forest Service, convincing the President at the time to carve out tens of millions of acres of forest reserves the night before an act of Congress that took away their ability to do that, passed. You think about people like Rachel Carson who started hammering about pesticides well before anybody else.”

Chris spoke quickly now.

Clearly he knew his history, our history but passion fired up the conversation with a dose of frustration that he had to talk this talk again. Washington was moving to limit protections, eviscerate safety standards, limit access to public lands, all of which flies in the face of such amazing groundwork meant to keep us and the environment safe and balanced.

“Those people didn’t rely on some bull process argument,” Chris said. “What I love is when these elected leaders, they decry the process until they come into office and then they use it to their advantage to basically stall progress. What we’re trying to do now in Bristol Bay is basically create as many administrative hurdles as we can to slow that mine down, until we find somebody who has the political courage to ultimately stop it.”

I asked, “How much more difficult is it for a conservation group which uses science and staff scientists, to go into a room with a government largely ignoring the established science of something like global warming and climate change?”

“I don’t think the government is ignoring climate change,” Chris said. “There are some people who have been put in those positions and those people will be gone in two or three years. They’re a blip on the radar. People who are within those agencies, they get it. They know climate change is happening, they’re doing their level best to make sure that good science and good information are getting out. There might be a few knuckle-draggers who are going to hold us back for a while but they’re not going to prevail over time…We can’t afford to wait three, four, five years to let logic prevail again. We’re taking that initiative to do a lot of that research and that original science that we would have counted on our federal agency counterparts to take care of for us, and that’s ok…that’s politics.”

I asked about national monuments and federal lands, which, not incidentally, are our lands. “Do you have your people in the trenches?” I asked.

“Oh yeah, this has been a campaign we’ve been hard at work on for years.” Chris said. “We’ve been involved, intimately, probably more than any other sportsman’s organization, to make sure we’re connecting sportsmen and women to those monuments, to those roadless areas, to these public lands that without the support and passion that hunters and anglers bring for them, could be lost.”

Father and son, teacher and student, in a perfect classroom

Consider “roadless.”

Roadless conjures up imagery of a country sparse with new immigrants and rich with possibilities, of westward expansion just being burned into our DNA. Roadless evokes memories of snowshoeing for two hours into a shadowed creek on some whispered mention of brookies you dare only hold for a moment out of pure respect. Roadless means a windy reach of the West Branch under the highest clouds you might ever imagine, with a five weight lashed to a three-day pack and a quart of Old Grand-Dad.

Building trust and memories above a Penobscot River pool

Roadless are places we need to know will always exist.

“Europe has these beautiful chapels that are hundreds of years old, Egypt has its pyramids and Africa has its Serengeti. You know what we have?” Chris asked.

“We have public lands, this network of national forests and public waterways and refuges and monuments that we all own by virtue of being born here. There is no other country in the world that has that legacy. It is one of the central characteristics of what it means to be an American. Unfortunately, without vigilance from people who fish and hunt, there are people in office right now who would trade that, they would either transfer it or they would sell it, quickly.”

No cell service wanted

Prior to our meeting, President Trump conceded to a request of Utah Republican Senator Orrin Hatch to reduce the 1.35 million acre Bears Ears National Monument. On December 4, Trump slashed it by 85 percent and the Grand Staircase-Escalante by almost half, opening the door for land to be leased or sold for mining, oil exploration, fuel infrastructure and worse, the possibility of corporations leasing away public lands for private uses. Unacceptable doesn’t even come close to describing the consequences.

Chris continued, “They do this at their own peril. The sportsmen community is slow to react…but if you start taking away their access to places to fish and hunt, you will get a reaction, a very strong reaction, very quickly…We haven’t had a king in this country for 240 years, so even though the President and others say they want to do all these things, they want to get rid of the Clean Water Rule, they want to get rid of Bristol Bay, they want to transfer our public land legacy, they want to shrink our national monuments, they don’t get to do that with a stroke of a pen. They have to go through a public process, a public process.”

Chris continued, “They do this at their own peril. The sportsmen community is slow to react…but if you start taking away their access to places to fish and hunt, you will get a reaction, a very strong reaction, very quickly…We haven’t had a king in this country for 240 years, so even though the President and others say they want to do all these things, they want to get rid of the Clean Water Rule, they want to get rid of Bristol Bay, they want to transfer our public land legacy, they want to shrink our national monuments, they don’t get to do that with a stroke of a pen. They have to go through a public process, a public process.”

Chris Wood believes the process will prevail because that’s how our forefathers, standing figuratively and literally at the headwaters of a new nation, designed it. It will because TU volunteers get their boots dirty. They work throughout the country, dramatically improving mining regulations in Maine, searching for native brook trout habitat, restoring 110 miles of Driftless area in Wisconsin where fish counts increased one hundred percent in one year. On some projects, Chris says they, “put the natural sinuosity back in the rivers.” How fantastic is a visual of sinuosity? It feels good just to say it.

True to their mission, TU staffers testify before committees then race to fish Arlington’s Four Mile Run where Keith Curley, Vice President for Eastern Conservation, sight casts from a dumped shopping cart because fishing is all over his own DNA. They provide millions for their Embrace a Stream program which , since 1975, has directed more than 1,050 specific grants worth more than $4.6 million. TU chapters contributed another $14 million in dollars and sweat equity towards protecting and preserving cold water fisheries. Chris said, “What’s really cool is the alchemy that our chapters then produce with that (money).”

Alchemy, an almost magical transformation or creation to make things better, beats the heart of Trout Unlimited.

“We’ve not only made fishing better, we’ve made it available,” Chris Wood said.

There’s a lesson for our government: to increase not reduce public lands, to use ecological logic when considering the science before you, to have a vision deeper than one election cycle and maybe leave The Hill to embrace a stream, consider sinuosity, ponder the amazing power of alchemy or balance for a short cast atop a shopping cart to meet people who care deeply about cold, clean waters and everyone who depends on them.

“TU chapters are taking kids fishing, getting them off their I-Phones, getting them out of doors.” Chris Wood