For three decades, award-winning Botswana-based filmmakers, National Geographic Explorers-in-Residence and wildlife conservationists Dereck and Beverly Joubert have focused their efforts on documenting and conserving Africa’s wildlife. They founded the Big Cats Initiative, which currently funds over 100 projects in 28 countries, with National Geographic in 2009. The program was established as an emergency action fund to come up with real conservation solutions to pressing problems surrounding these majestic felines and the alarming reduction in the lion population over the past 50 years—from 450,000 to just 20,000.

In 2006, the Jouberts decided to expand their conservation outreach efforts and formed Great Plains Conservation, bringing together local communities and conservation tourism. They are now funding large tracts of land that can be protected for the local wildlife. Today that land totals about 1.5 million acres in Africa, critical land for corridors and threatened and endangered species.

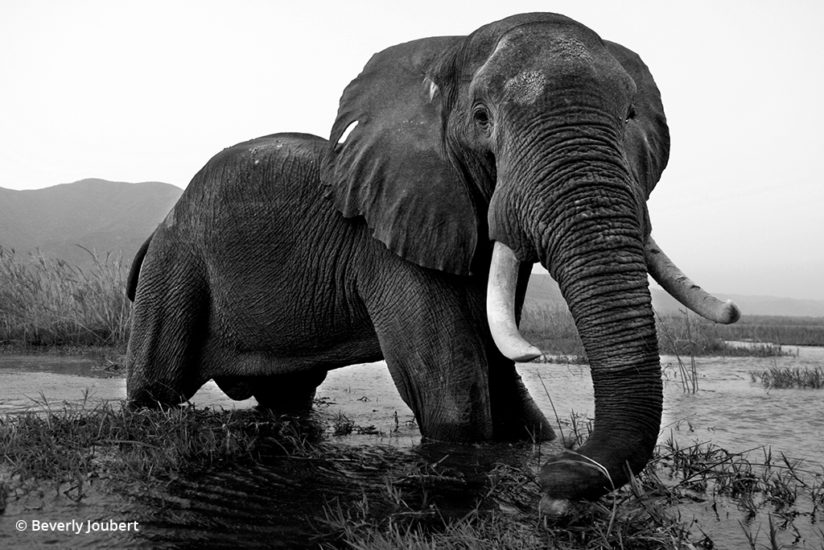

The couple’s films, including “Eternal Enemies,” “Eye of the Leopard,” “The Last Lions,” “Reflections on Elephants” and “Soul of the Elephant,” have earned them eight Emmys and many other awards. It is estimated that more than a billion people have viewed “Eternal Enemies,” which focuses on the interaction between a pride of lions and a clan of hyenas. Dereck films and writes, while Beverly co-produces with Dereck and records sound in addition to creating powerful still imagery celebrating the beauty and wonder of wildlife.

On March 3, 2017, all of their efforts nearly came to an untimely end. A buffalo charge nearly claimed the life of Beverly in the Okavango-Delta in Botswana while Dereck suffered major injuries. The couple endured 11 hours of awaiting medical assistance on what was Dereck’s 61st birthday and coincidently World Wildlife Day. Beverly was impaled under her right arm, shattering her collarbone and missing every major artery as it traveled up through her throat and month, stopping short of her eye by a few millimeters. A collapsed lung, 120 sutures, 20 hours of surgery and the reconstruction of 21 shattered facial bones have only increased her passion to save Africa’s wildlife. “We are sharper, more focused and resolute to do what we can to change a version of the future where there are no buffalo, no wildlife, no rhinos to save, no lions,” she says.

Outdoor Photographer: How are you both feeling?

Beverly Joubert: After eight months of rehab, we’re back up and running and we’re more committed than ever to conservation. We’re living a dream. We are taking the power of the incident to be more effective in conservation.

OP: How did the two of you get on the road to what you’re doing these days?

Dereck Joubert: We are both from South Africa and met in high school. We always felt that to understand the continent we were born in, that we needed to get out into the wild and explore. We started up in Botswana strategically with the top predators so we could understand everything else and fell in love with the place, with lions and of course with each other. Losing the big iconic species would create a devastating impact on our ecosystem, and we can’t let that happen.

BJ: We arrived in Botswana in 1981 through the Okavango Delta and fell hopelessly in love with it and knew we wanted to go back. Then we had an opportunity to join a lion research station in Chobe and studied lions there for years, mainly at nighttime. These lions hunted predominantly 85 percent at night. Very seldom would you see them active during the day. Through the night, we were documenting things that hadn’t been written up before.

We knew that it would take more than scientific papers to get the word out about them to a wider audience. We decided to capture what we were seeing on film. Neither Dereck nor I were trained as filmmakers, so learning how to make films was part of an almost organic process of being a documentarian founded on basic story telling techniques rather than technical skills.

OP: It must have been very difficult recording the lions at night, especially with film.

DJ: We used tungsten lights, basically car lights, and we developed techniques to fix the lights in trees and various points around waterholes so animals could approach us at their pace, but those were the primitive days, and we were making it up as we went along. We struggled with the technology. That’s all we had in the eighties. Then we moved to Redhead quartz lights. At first we were using 16mm cameras, then upgraded to Super 16, then to 35mm, then to HD, to 1080 and then to 4K, and at the moment I’m shooting on 8K. That’s the evolution. The first camera was an Arriflex 16SR, and now I’m using the RED.

OP: Beverly, what camera equipment are you currently using?

BJ: I’ve been shooting predominantly with the Canon EOS-1D X. I really love Canon’s 600mm f/4 lens. But since the accident, I have to say, I’ve been shooting a lot with the Sony a9. My shoulder was shattered in five places, so I felt that starting again with a lighter camera would be better. But the camera and the lenses for it are exceptional, so I’m now juggling two brands, Canon and Sony. If I’m doing international travel, I’ll carry the lighter Sony. You can put the Canon 600mm on the Sony with a converter, but I then I have to focus manually. The longest lens for the Sony is 400mm. Often I shoot with a beanbag low on the ground. Our vehicle is often our tripod, and we have fluid heads attached to our Land Cruiser.

OP: While camera technology continues its dramatically upward movement, the opposite can be said about the lion population. What is that attributed to?

BJ: That’s right. Fifty years ago it was 450,000, and now we’re down to 20,000. There are similar figures across all the big cats. There were 35,000 tigers, now they’re down to 3,000. Cheetahs have dropped below 7,000. Leopards are down from 700,000 right down to 50,000. They are so elusive, it’s very hard to count them.

DJ: The reasons for these declines is habitat loss, conflicts with livestock, a new trade in lion skeletons that is started up, and also safari hunting. If you look at the 20,000 lion population number now, about 3,500 of those at best are male lions. Most safari hunters want to kill a male lion, and they’re shooting those legally at a rate of 660 a year. This is clearly not sustainable.

BJ: So the question is, “What can be done about it?” Dereck and I, as conservationists, have wanted to make an impact and help protect them. We believe that film was the obvious place to go, and producing films with National Geographic has helped us reach a global audience. But we realized about 10 years ago that even though the films were successful, many of the atrocities are continuing to the extreme. That’s when we started the Big Cats Initiative at National Geographic that supports scientists and conservationists working to save big cats in the wild. We’ve supported over 100 projects to protect seven iconic big cat species in 28 countries and built more than 1,600 livestock enclosures to protect livestock, big cats and people. Communities are learning how to protect the lions. Each project is vastly different in each country because of different cultures, the environment and different situations. We have seen successes. We have seen a place like southern Maasailand in Kenya where lions were being killed at a rate of 50 per year come down to zero in that time. Communities are seeing the benefits and are becoming future conservationists.

Another way of creating a positive impact is by looking at the land that is vulnerable and creating corridors between national parks or conservancies. That’s why in 2006 we created Great Plains Conservation. Looking at how to protect land and the best way to make it sustainable and to bring in the communities. Environmental tourism has been very successful. We now have nine camps in Botswana, Kenya and now just opening in Zimbabwe.

DJ: The very first place we took over was a hunting concession in the Selinda area, in the northern part of Botswana. We shut down the hunting and turned it into a reserve. Today we can see the incredible difference from when we took it over. Animals were frightened and ran from man in the beginning. You would only see elephants at dusk and dawn when they would come for a drink, whereas today we have elephants moving through the camps, people getting very close to elephants on game drives; it’s a remarkable success story. In addition, we created a net financial benefit to the nation of over 2,500 percent and increased jobs and basic food in the plates for over 7,000 people.

The solutions in Africa are multi-pronged. But there is an interesting relationship between commercial enterprises, conservation, communities and governments. Without all of them, you can’t have a solution. Commercial enterprises such as tourism bring in millions of dollars a year. Communities benefit and buy into saving gorillas in Rwanda or lions in Kenya. The communities become real stakeholders in the management of these wild lands. There’s massive pressure from increasing populations of communities to get a piece of the pie, so demonstrating that there are benefits is important. But we have to also understand that there are there are benefits to us all that cannot be calculated in dollar terms. Our spiritual and ecological intelligence depends on this connectivity to nature; how does one quantify that?

BJ: Conservation is our ultimate goal, but filmmaking is our main medium, speaking to the world, and I am also passionate about the still image. I’ve enjoyed being able to have fine art exhibitions around the world, another platform to talk about conservations issues. We use social media, clips from the films and actual talks to get our message across. We reached 195 million people by going to Beijing over a few days. We spoke in a respectful way about the problems of African wildlife rather than an accusatory way. We have to work together to get the political change we need. Africa should not be the playground for the rich hunters when animals are on the decline.

DJ: There’s propaganda put out by hunting organizations. You’ll hear this: “The only way for certain animals to survive in Africa is to hunt them.” What sort of person enjoys going out and pointing a gun at an elephant and blowing its brains out? Ultimately, it comes down to that. All the other stuff is making noise, in my opinion. Safari hunting industry is not about eating the kill. In fact, it is probably colonial and elitist and in some cases insulting to many local people in Africa to suggest that they can only live off the meat it provides. We are better than that. In many places it’s called recreational hunting. I consider recreational sports to be tennis or golf, not going out and shooting animals for sport.

OP: Your film “Soul of the Elephant” really gets across the reality that these noble creatures are sentient beings.

BJ: They are sentient beings, and in Botswana our people talk of them as the animals with “eyes that can think.” We brought on a crew along for two to three weeks to cover the behind the scenes of Dereck and I padding down one of the longest rivers in Botswana, a 120-kilometer canoe journey, and this river, the Selinda Spillway, cuts through the highest density of elephants in the world. We were getting close, very close, but we all felt totally safe and in many ways at one with elephants because of the way they accepted us, even the foreign crew.

OP: How is the future looking?

DJ: I’m actually very positive about the future. The Big Cats Initiative is making a difference. We’ve been able to work with the Botswana government to move 100 rhinos to safety, and we’ve acquired hunting land to convert in Botswana and Zimbabwe. Botswana banned all hunting in 2014. China bans ivory, ivory is crushed in Times Square…it would have been very difficult to do all this 25 years ago. In fact, it would have been science fiction! We were fighting a war back then, literally, for wildlife. We’ve been able to reach out to the public and raise the money and awareness. We’re getting articles out. We’re getting films out. It’s critical.

OP: It’s incredible to think of what you two have endured to get your message out to the world when taking into consideration your recent history.

BJ: Sometimes we actually see the buffalo as a messenger. In Africa, the wilderness areas are in trouble. Are we doing enough? No, we’re not. It’s a message. Come on. Wake up. Here’s another chance. Keep going. We are beyond passionate.

DJ: It’s an obsession; we really can’t stop.

BJ: The atrocities are still happening. In a period of 50 years, we’ve seen a decline of 95 percent. It’s alarming. The incident was a reminder that we’re running out of time. The wilderness areas are truly running out of time. Humanity will be overtaking these beautiful areas. Humankind will do the logging and the slashing and burning and the poaching. Losing land by the degradation of cattle. It’s really our commitment to try and stop that.

DJ: But we are determined that this story, just like the buffalo incident and many others in our lives, will end well, for us all.

Learn more about the Jouberts’ work at wildlifefilms.co and beverlyjoubert.com.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Kitenden Wildlife Corridor

Photographing a new conservancy corridor in Kenya conceived to balance the needs of human and elephant. Read now.

The post Wild Exposures appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.